EWP2011 PROJECT OVERVIEW:

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Hazardous Weather Testbed (HWT) in Norman, Oklahoma, is a joint project of the National Weather Service (NWS) and the National Severe Storms Laboratory (NSSL). The HWT provides a conceptual framework and a physical space to foster collaboration between research and operations to test and evaluate emerging technologies and science for NWS operations. The Experimental Warning Program (EWP) at the HWT is hosting the 2011 Spring Program (EWP2011). This is the fifth year for EWP activities in the testbed. EWP2011 takes place across four weeks (Monday – Friday), from 9 May through 10 June. There are no operations during Memorial Day week (30 May – 3 June).

EWP2011 is designed to test and evaluate new applications, techniques, and products to support Weather Forecast Office (WFO) severe convective weather warning operations. There will be three primary projects geared toward WFO applications this spring, 1) evaluation of 3DVAR multi-radar real-time data assimilation fields being developed for the Warn-On-Forecast initiative, 2) evaluation of multiple CONUS GOES-R convective applications, including pseudo-geostationary lightning mapper products when operations are expected within the Lightning Mapping Array domains (OK, AL, DC, FL), and 3) evaluation of model performance and forecast utility of the OUN WRF when operations are expected in the Southern Plains.

More information is available on the EWP Blog: https://hwt.nssl.noaa.gov/ewp/internal/blog/

WEEK 4 SUMMARY:

Week #4 of EWP2011 was conducted during the week of 6-10 June and was the final week of the spring experiment. It was another pretty “average” week for severe weather, certainly paling in comparison to Week #3. During this week, NSSL and the GOES-R program hosted the following National Weather Service participants: Bill Bunting (WFO Fort Worth, TX), Chris Buonanno (WFO Little Rock, AR), Justin Lane (WFO Greenville, SC), and Chris Sohl (WFO Norman, OK). We also hosted special guest Dr. Pieter Groenemeijer, Director of the European Severe Storms Laboratory near Munich, Germany, for several of the days. Pieter was visiting both sides of the HWT to learn about the process in order to develop a similar testbed for the ESSL in 2012.

The real-time event overview:

7 June: Failure of CI over eastern ND and northern MN; late action on post-frontal storms in central ND.

8 June: Squall line with embedded supercell and bow elements over eastern IA and southern WI.

9 June: Afternoon squall line over southern New England and NY; evening supercells western OK and southern KS.

The following is a collection of comments and thoughts from the Friday debriefing.

NSSL 3D-VAR DATA ASSIMILATION:

One major technical issue was noted but not diagnosed. It appeared that at times, the analysis grids were offset from the actual storms, so it is possible that there were some larger-than-expected latency issues with the grids.

It was suggested to add a “Height of maximum vertical velocity” product. However, we hope to have the entire 3D wind field available in AWIPSII. We also hope to have a model grid volume browser, similar to the radar “All-Tilts” feature within AWIPSII. We used the WDSSII display for the wind vector displays. The forecasters noted that the arrows were plotted such that the tail of the arrow was centered on the grid point. It should be changed to the middle of the arrow.

The vorticity product was the deciding factor on issuing a Tornado Warning for the Thursday storm north of Wichita.

Bad data quality leads to bad 3DVAR. In particular, it was noted several times that side-lobe contamination in the inflow of storms was giving false updraft strengths. Improper velocity dealiasing is also detrimental to good 3DVAR analysis. There is an intensive data quality improvement effort ongoing as part of the WOF project.

The downdraft product occasionally took a maximum “downdraft” at the upper levels of the storm and projected it to the surface. There’s not a lot of continuity, and it is difficult to discern consistent features associated with the storms.

Would also like to use the products with less classic type storms, like low-topped convection, microbursts, etc.

David Dowell, who was visiting from GSD this week, is working on a next-generation assimilation using Kalman filtering, but requires more CPU power. Jidong Gao at NSSL might create a blended technique (with Dowell) that requires less CPU power, something like a 3.5DVAR, which uses 3DVAR for hot-start analysis with radar and model analysis background, and then runs a cloud model out 5 minutes based on that and use it for the first guess on the next analysis, and so on. This means we would be able to get more fields like T and P for cold pools, downdraft intensity and location, for storm types other than supercells.

OUN-WRF:

There were very few opportunities to evaluate OUN WRF data this week. Our only event within the domain was on Thursday with a late domain switch for evening half of activities within OK and KS, but convection was already on-going and evaluation concentrated on other experimental EWP products. The model suggested a few more storms that weren’t there. One of our forecasters who use the data during regular warning operations in their WFO commented that the updraft helicity product helps with predicting storm type, but that it tends to overproduce cold pools and outflow.

GOES-R Nearcast:

The Nearcast principle investigator, Ralph Peterson, was on hand this week. He posed the following questions to the forecasters: Did you find the Nearcast products useful to ID the areas likely for convection initiation, and to predict the timing and location in pre-convective atmosphere.

The Nearcast products were primarily used during the early parts of the day to facilitate the area forecast discussion and afternoon/evening warning location decisions. One forecaster noted that the Nearcast data behind squall lines becomes less useful with time due to intervening cloud cover.

The forecasters were asked if it would be useful to provide extended forecast hours but at the expense of greater data smoothing. They liked to have the higher-resolution data to as far out as it is useful to have it.

The forecasters were also asked if they would have used the observation/analysis alone without the forward extrapolation, and the answer was that it wouldn’t have been as useful, since it is better to see how the current environment will evolve.

Showed an arch of destabilization between 2200-0300 across the eastern halves of OK and KS… storms formed on the western edge of this gradient and forecaster did not expect the storms to diminish anytime soon and thus increased warning confidence… stronger wording regarding hail/wind potential in warning was issued.

There seemed to be small scale features in the fields, areas of relative maximum that were moving around… would be nice to compare to radar evolution and see how those areas affected the storm structure.

Helped understand why convection occurred and where it would occur… definitely the 1-6 or 1-9 hour timeframe was the most useful aspect of it.

Having a 4-panel set up of the individual layers in addition to the difference field to help increase the understanding of the product.

The color-table in AWIPS was poor… Also, the values were reversed from those in NAWIPS and on the web. The individual layers of PW were also not available in AWIPS.

GOES-R Convective Initiation (UW and UAH):

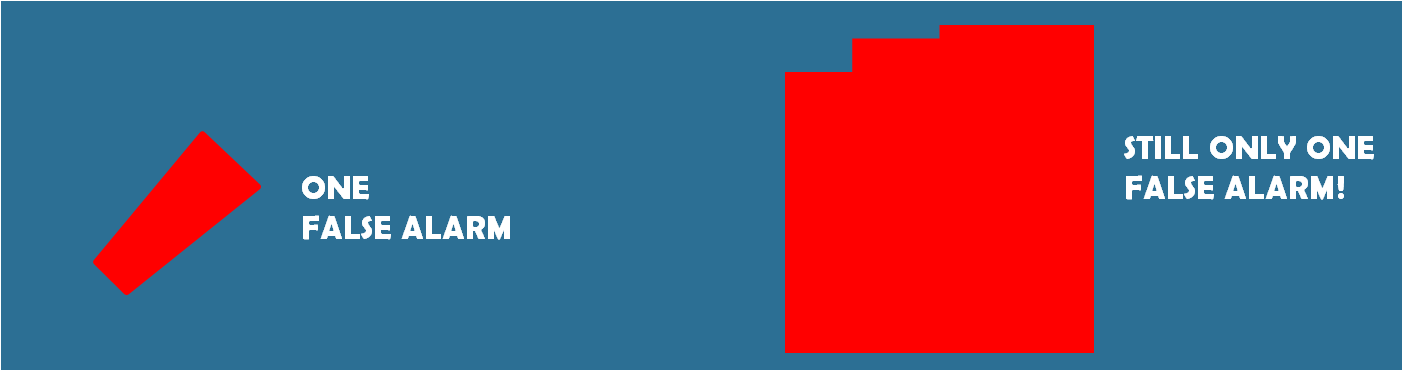

The forecasters were asked if they compared the two CI products side-by-side. The UAH product is more liberal in detections, has a higher resolution (1 km), and uses visible satellite data during daytime mode. The UW product is more conservative in detections, has a 4 km resolution, uses only IR data, and masks output where there is cirrus contamination.

During the daytime, most forecasters were able to spot initiation in the visible satellite data, and thus the CI products were not all that useful for heads-up. They did mention there could be value during nocturnal events, but the EWP doesn’t operate after dark, so we couldn’t test.

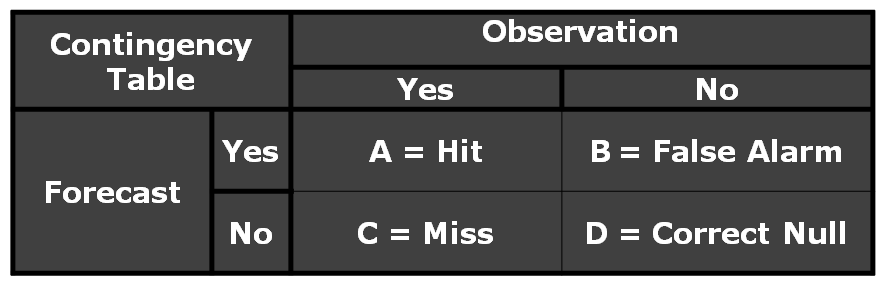

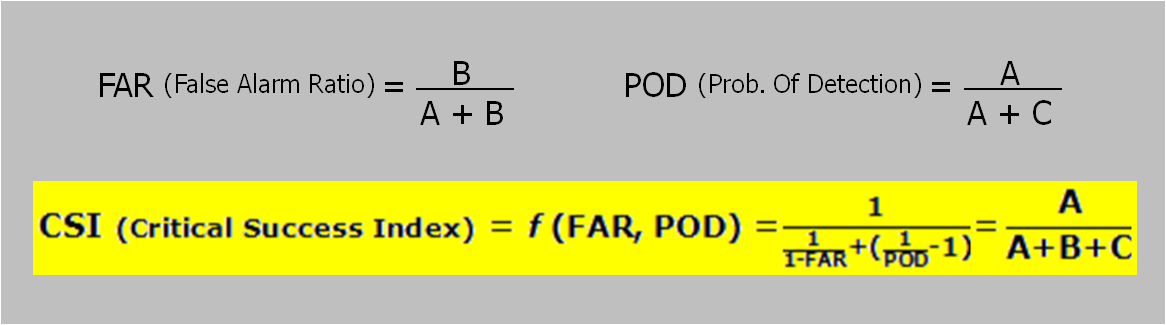

The notion of probabilistic output was once again brought up. Instead of a product that was “somewhere in the middle” of good detections and false alarms, a probabilistic product could be more useful. And a comment was made to bring both groups together to product a single probabilistic product.

In some cases, the products failed to trigger on clumps of cumulus that looked similar to other clumps that were receiving detections.

One forecaster raised a concern about consistency with respect to the FAA using the product for air routing. If the CI product was automated and used by FAA, how would that conflict with human-created TAFs and other products?

A forecaster found that the UW cloud-top cooling rates useful to look for the timing of the next area of developing convection.

Even though CI didn’t always occur… false hits were useful in identifying clouds trying to break the cap.

GOES-R OTTC:

The one day we would have expected a lot of Overshooting Top detections, Thursday over Kansas, there were lots of missed detections. Otherwise, the forecasters felt that they could ID the overshooting tops well before the algorithms, except perhaps at night (when we don’t operate). Chris Siewert mentioned that the spatial resolution of current imager is too great (4x4km), and OT detection works better on higher-res data sets. The temporal refresh rate also affects detection; sometimes feature show up between scans.

GOES-R pGLM:

We only had one half of an event day to view real-time pGLM data, the Thursday evening OK portion of our operations. Some of the storms to the east had higher flash rates, but this was an artifact of the LMA network’s detection efficiencies. Flash rates would pick up a short time before increases in reflectivity.

One forecaster has access to real-time LMA data in the WFO and had some comments. They get a lot of calls wanting to know about lightning danger for first and last flash and stratiform rain regions. It is also good for extremely long channel lightning – might get a rogue hit well away from main core, and sometimes anvils well downstream of main core can get electrically active.

There are more GOES-R details on the GOES-R HWT Blog Weekly Summary.

OVERALL COMMENTS:

The challenge, which was good, was integrating that info with all the other data sets, but also on how to set up the workstations, and best practices to use it. Need six monitors!

Need pre-defined procedures. Forecasters used the “ultimate CI” procedure heavily and liked to see what we think they should be combining to help enhance the utility of the products. (However, it is not always clear to the PIs which procedures would be best, as the experimental data has not yet been tested in real-time).

Like the two shifts. Get to experience both types, a nice change.

I sometimes got too tied into warning operations rather than looking at experimental products. It’s Pavlovian to think about the “issuing warnings” paradigm. (We tried to emphasize that getting the warning out on time wasn’t a priority this year, but using the warning decision making process to determine how best to use the experimental data sets, but “comfort zone” issues inevitably rise up.)

Training would have been better if done prior to visit, using VisitView or Articulate, and spend training day on how to use products rather than coming in cold.

Two weeks is nice, but April-May is a tough time to add another week, or even one or two X shifts for pre-visit training.

I went through most of training on web before visiting, it was abstract. But once here, went through it again in a different light.

EFP interaction was tough – it was too jammed at the CI desk. We felt more like an “add-on” rather than an active participant.

The joint EFP/EWP briefings were too long, and covered aspects we didn’t care about. There were competing goals. We should have done it in 15 minutes and moved on. Need microphones for briefing. Didn’t need to hear hydro part. Need to set a time guideline at briefing for all groups. Also, the information being provided was more academic than pure weather discussion.

The HWT needs more chairs. Also, two separate equal sized rooms would be better than the current layout.

A LOOK AHEAD:

EWP2011 spring experiment operations are now completed.

CONTRIBUTORS:

Greg Stumpf, EWP2011 Operations Coordinator and Week 4 Weekly Coordinator

Chris Siewert, EWP2011 GOES-R Liaison (from the GOES-R blog)