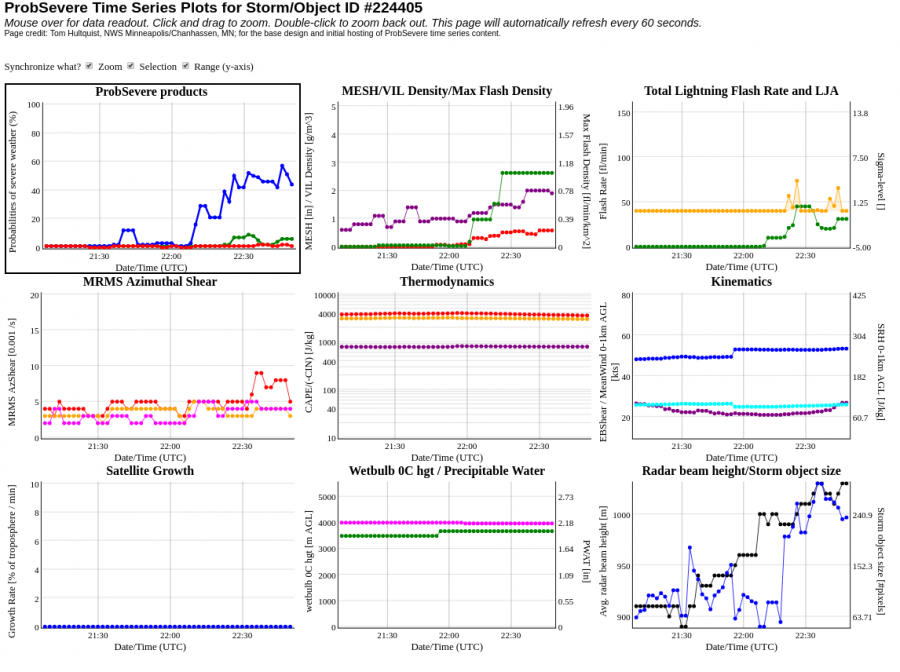

The GLM data is showing a lot of utility and provides useful information on storm trends, intensity, and storm mode. However, the biggest issue is how to visualize all this information and tie it to the meteorology; the “physics-science” side of things in order to tie everything together.

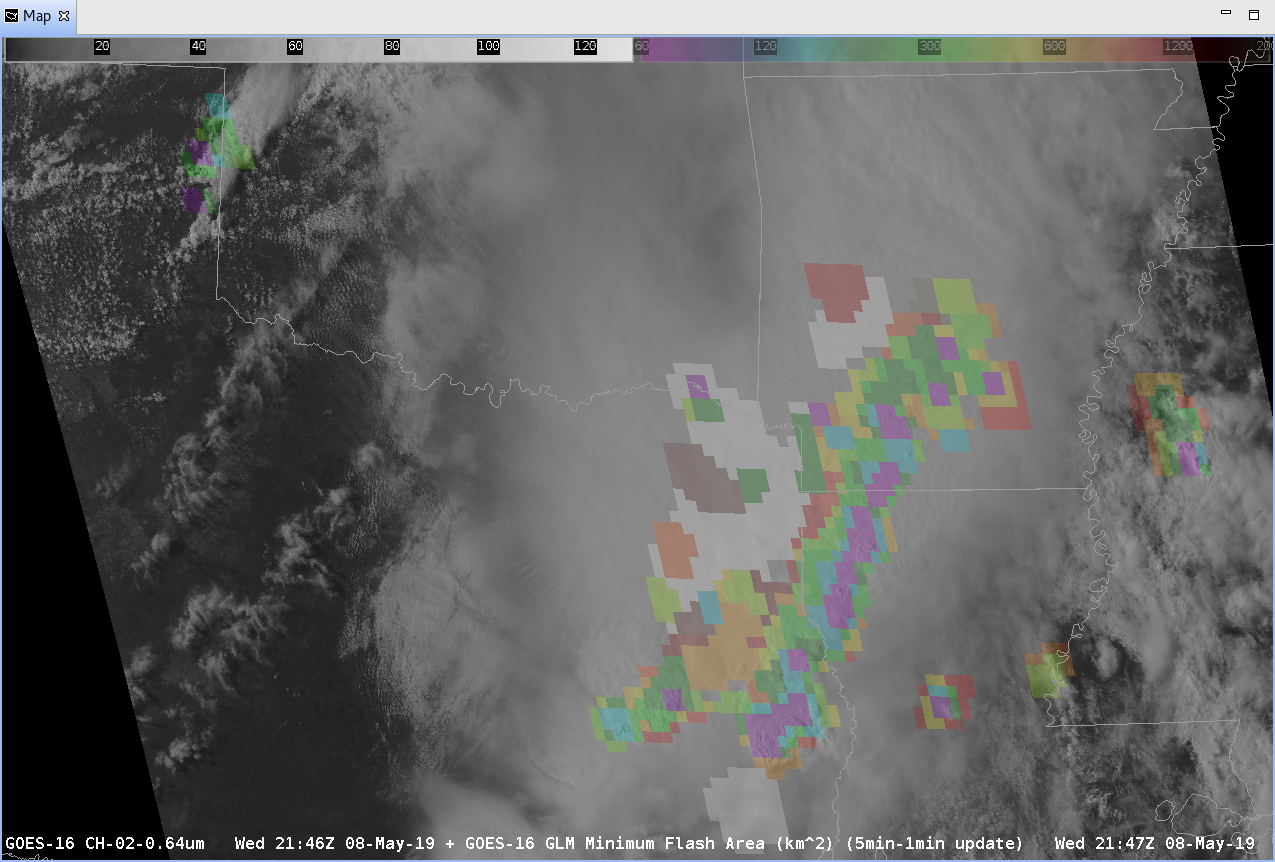

Here is the first attempt and why:

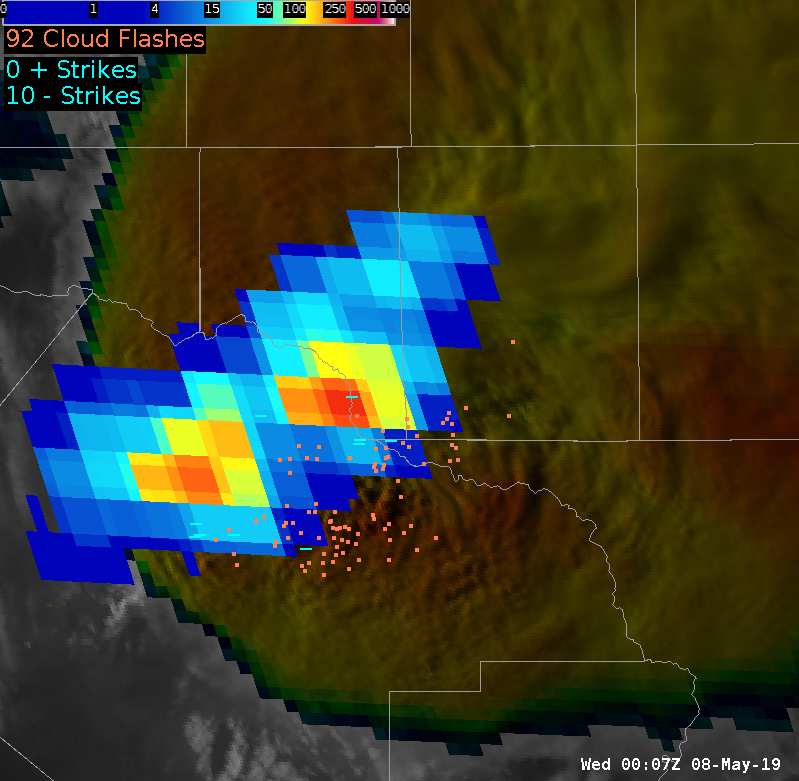

Top left panel – 5-Minute Flash Extent Density with 1-minute updates (enhanced color curve): this is a good way to see trends with the GLM data as it is a 5-minute window updated every minute. Shows increases/ in lightning flashes with time with a “smoother” display rather than just every 1-minute frame.

Top right panel – 1-minute Minimum Flash Area (enhanced color curve): shows where the smallest flashes are occurring. Rough reason; small flashes corresponds to strong updrafts with lots of turbulence limiting the extent to which flashes can develop. So, small flashes (around or under 100 km2) should correspond to strong updrafts. Works with both multi-cellular, super cellular, and pulse convection. Don’t use the 5-minute with 1-minute update because the tendency I’ve seen so far is that it can result in an area of small flashes that is way to large for an individual storm updraft as it covers where it has been for the last 5 minutes!

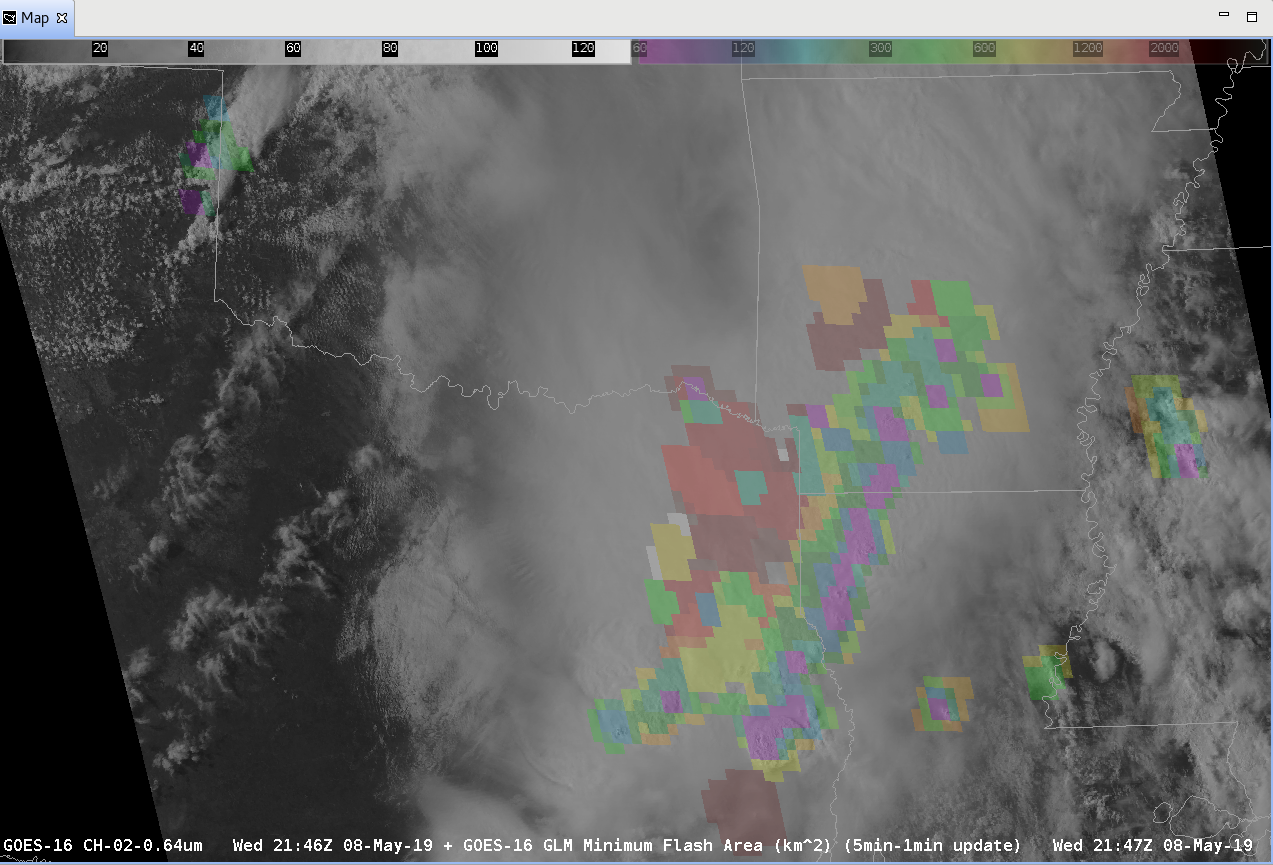

So, how to tie this into the meteorology. There needs to be some way to show “ground truth” outside of the ground-based lightning detection networks. So, let’s give this a try:

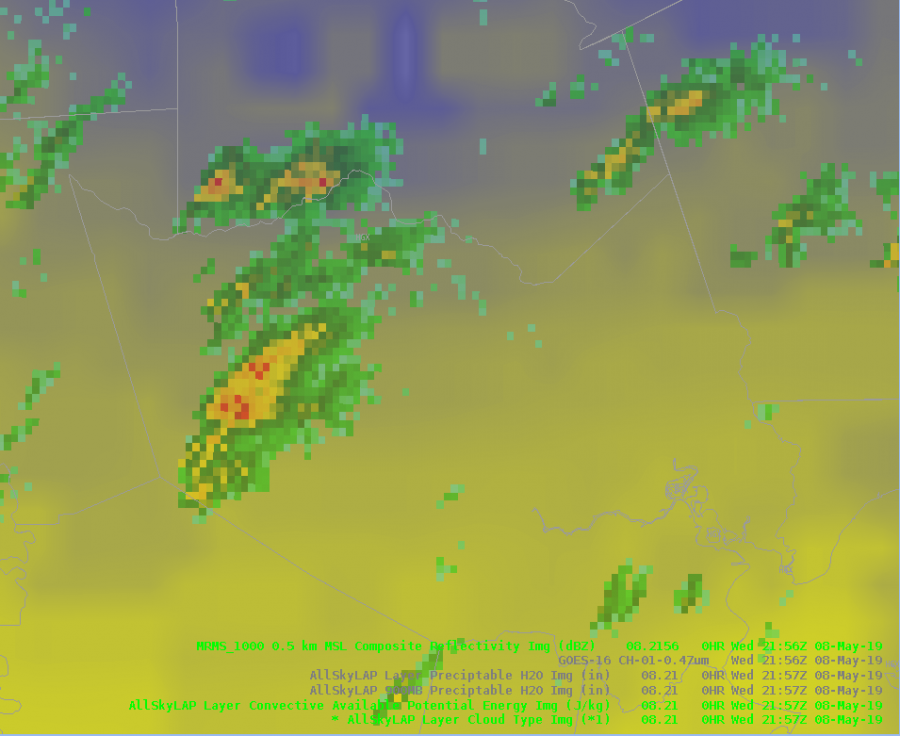

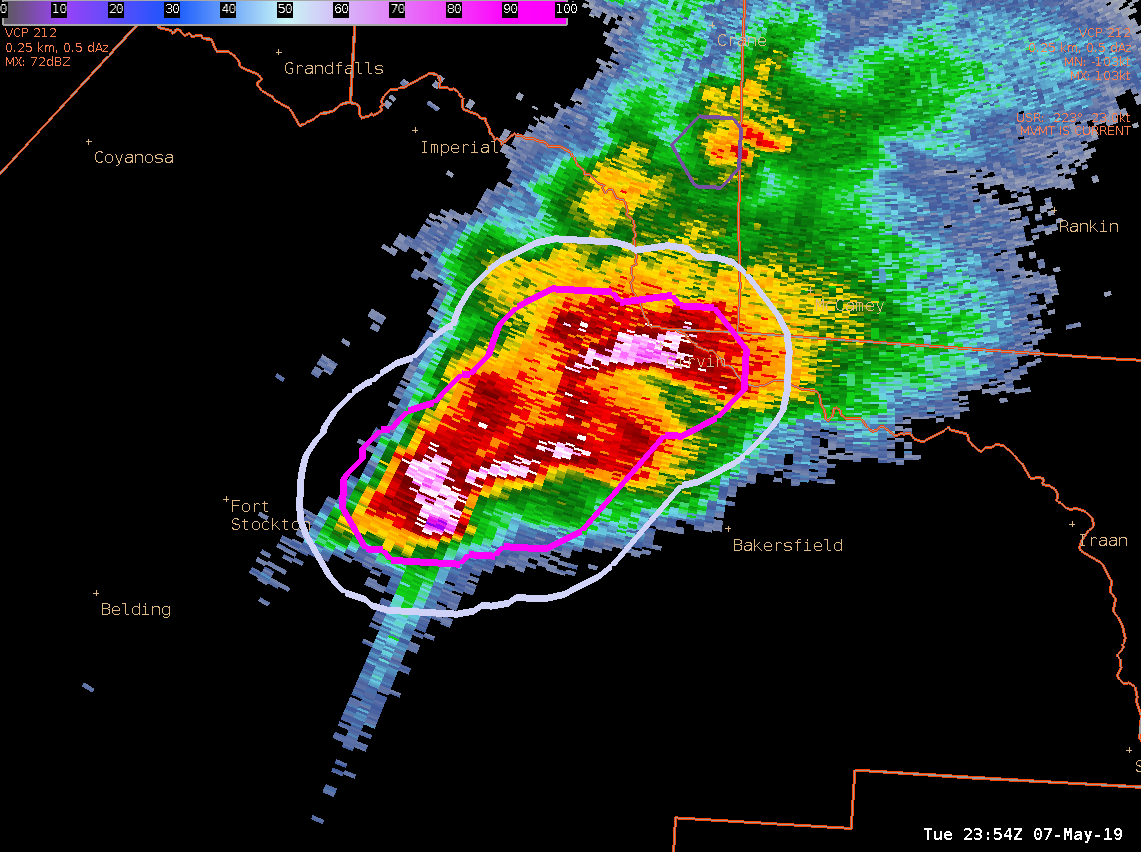

Bottom left panel – MRMS composite reflectivity at -10 C. This shows strong convective cores that are capable of producing mixed-phased precipitation needed for lightning. MRMS because it can cover areas with storms that are within the Cone-of-Silence for any given radar. Going with -10 C gets above the melting level at 0 C and below the -20 C where the majority of particles should be switching over to more ice crystals than liquid and/or large hail.

Bottom right panel – 3 to 6 km Merged Azimuthal Shear. If done right, this should show when mid-level mesocyclones are starting to strengthen and where rotation would be the strongest. Strong updrafts that are rotation can help a storm produce small flashes (again, the whole turbulent mixing in and around the updraft thing).

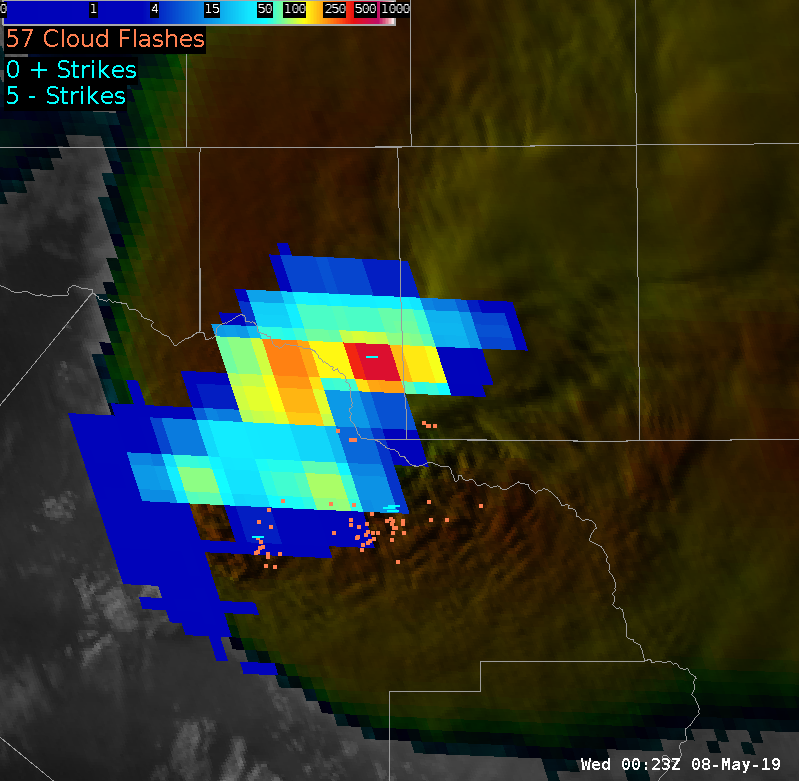

Is this the best way to do this? No idea! It’s a start though and as we go through the following 6 frames, you can hopefully see how this plays out. Watch the southern-most storm have high Flash Extent Density counts while the Minimum Flash Area remains around 60 km2. Although there isn’t a strong sign of rotation in the AzShear product, the GLM data shows that there is a strong updraft that has maintained strength over the last 6 minutes.

Watching the northern storm, AzShear shows stronger rotation and a quick check of the base data (not shown Z, V, SRM) shows that there was a weak but persistence mesocyclone with the northern storm. With time, the AzShear product shows strong cyclonic shear with this storm and we start to see the FED increase while flash sizes decrease. It takes some time but after around 5 minutes, the Minimum Flash Area had bottomed out around 60 km2.

This isn’t perfect by any means. Another issue to look it is how to incorporate this into warning operations because this is a lot to look at. At this point, GLM data may be too much to add in a single-person warning situation.

Something to consider…