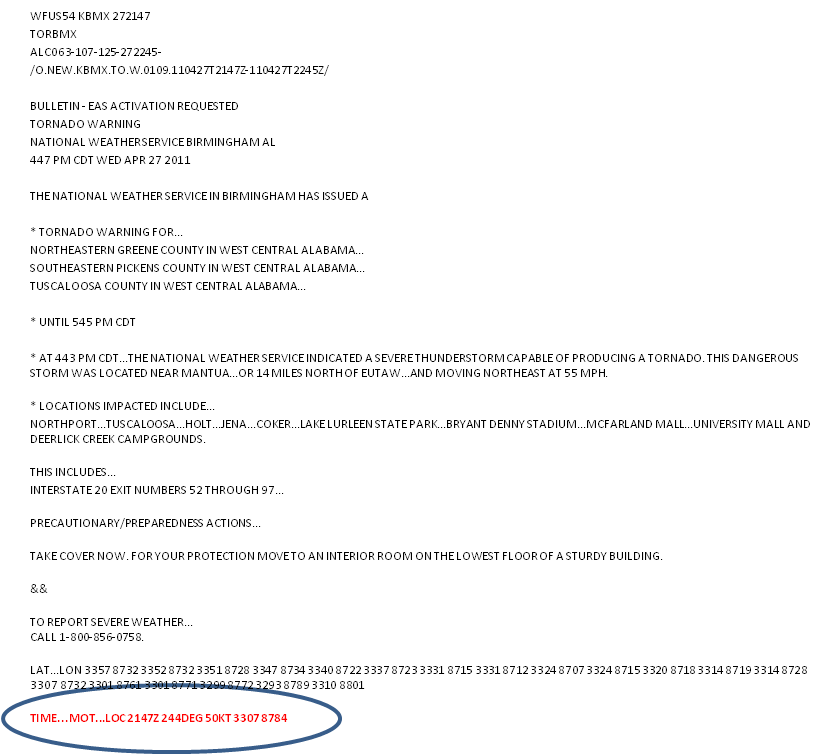

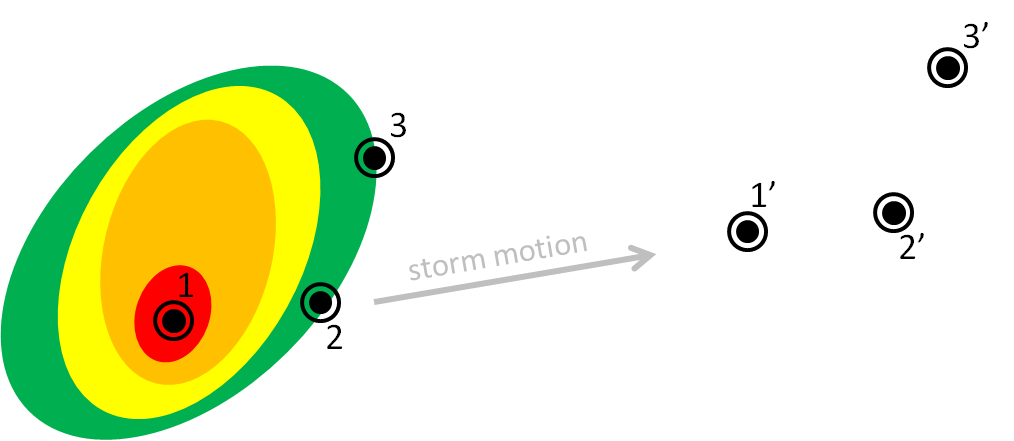

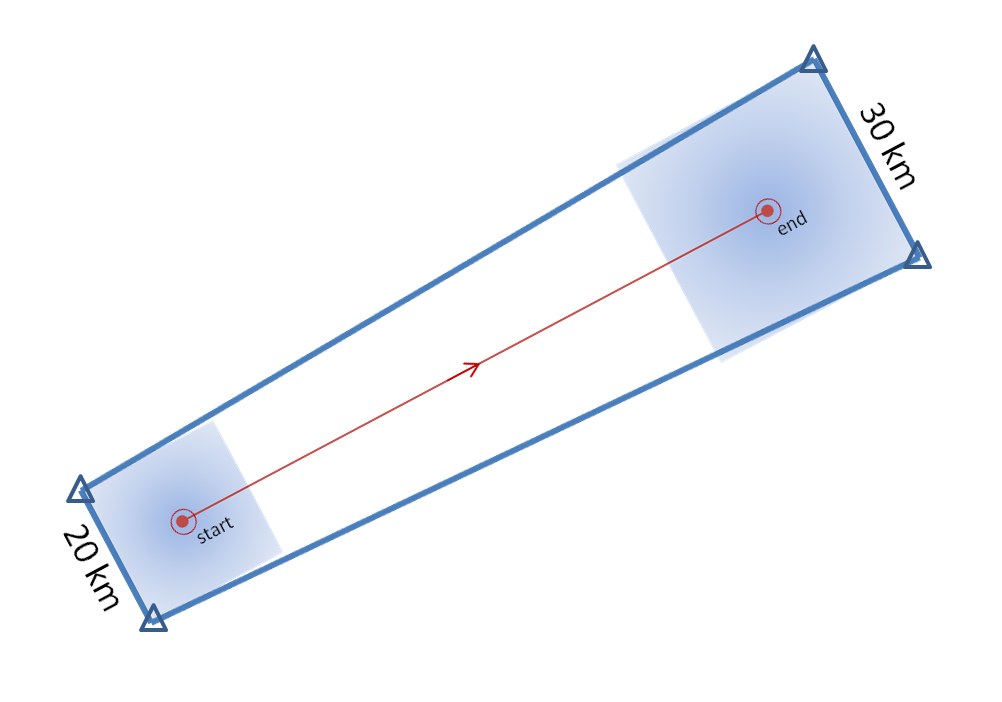

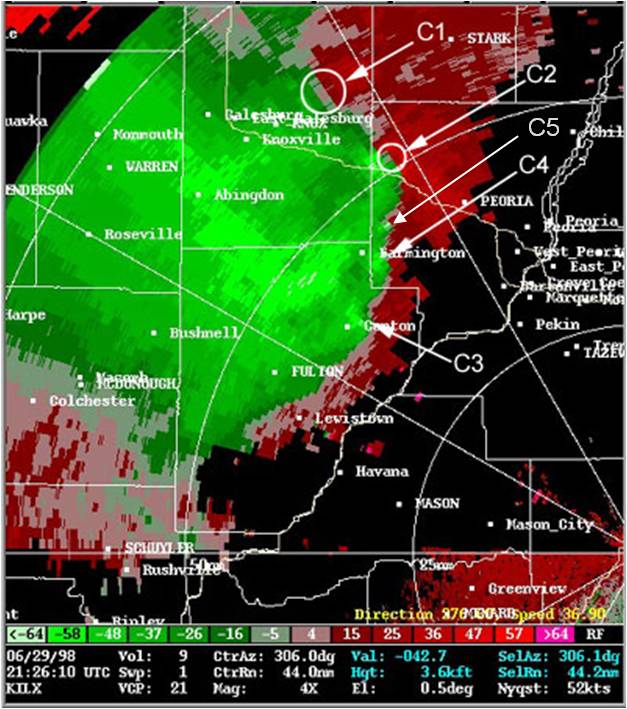

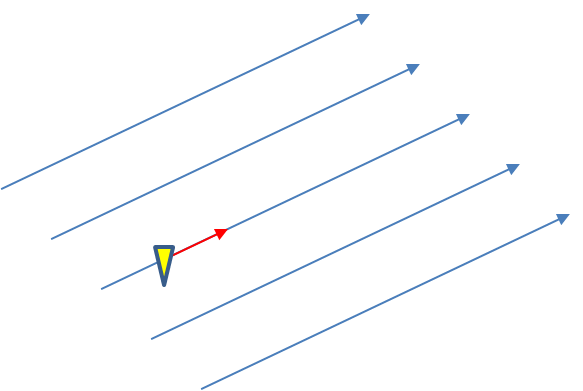

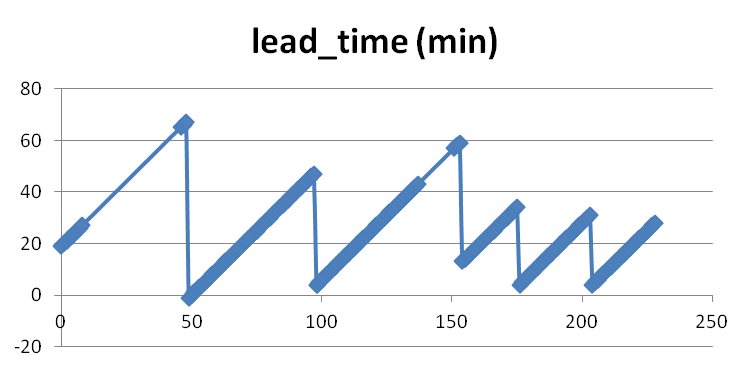

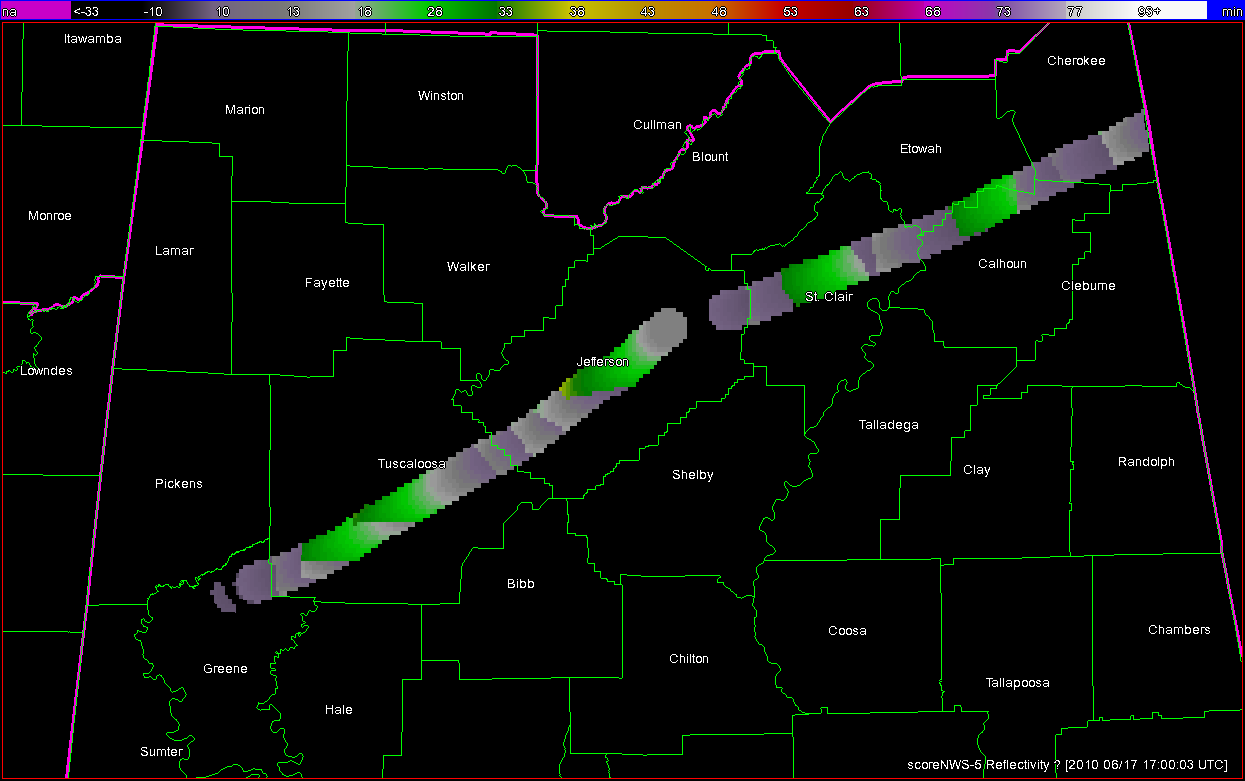

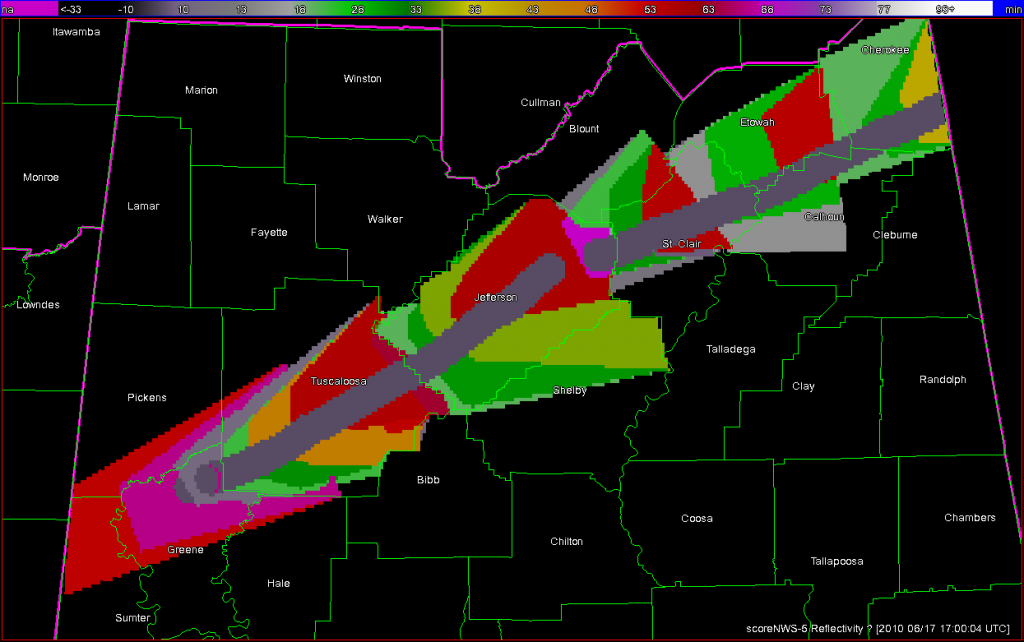

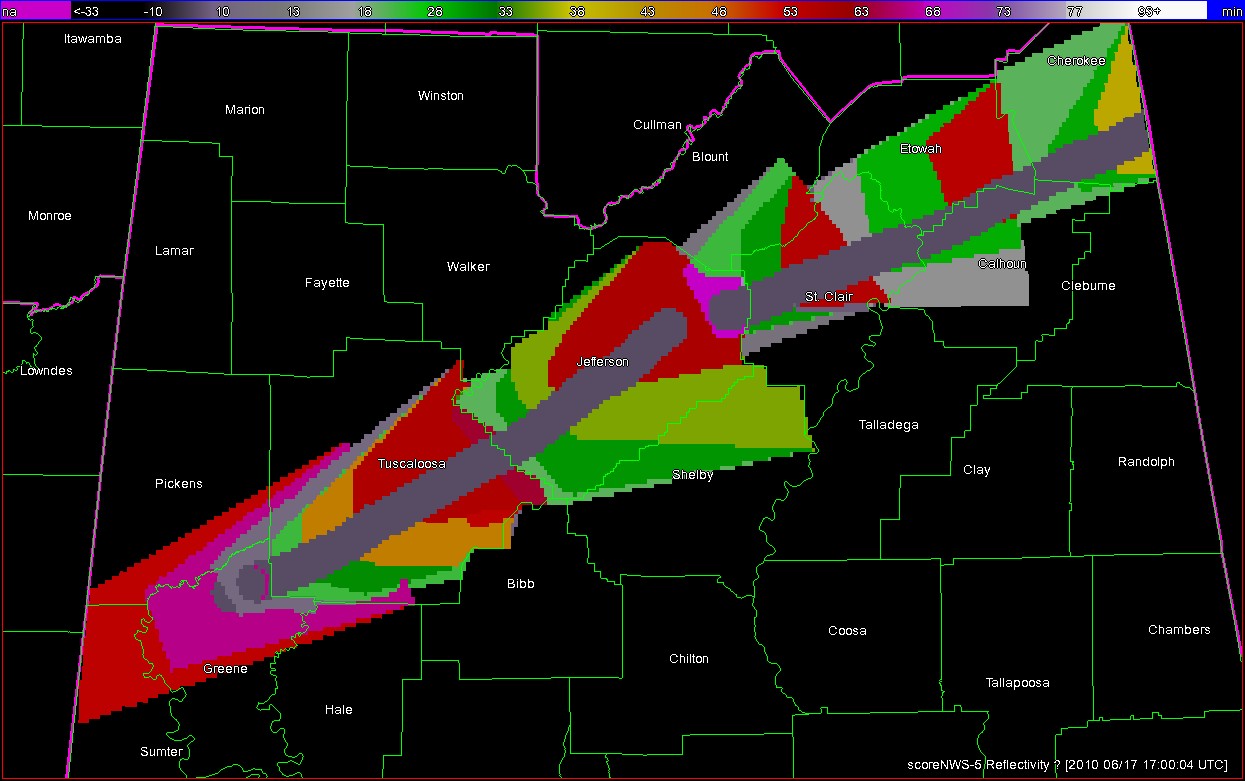

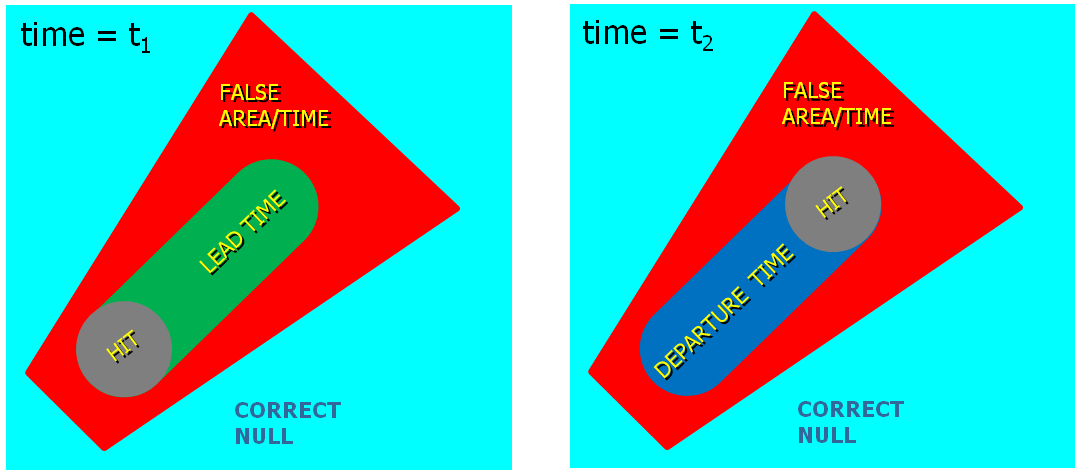

Here I’m going to describe the “Threats-In-Motion”, or TIM concept that was presented at the 2011 National Weather Association Annual meeting. Essentially, once a digital warning grid is created using the methodology presented in the previous blog entry, the integrated swath product would start to translate automatically. The result would be that the leading edge of the polygon would inch downstream, and the trailing edge would automatically clear from areas behind the threat. We hypothesize that this would result in a larger average lead time for users downstream, which is desired. In addition, the departure time of the warning should approach zero, which is also considered ideal. The concept is first illustrated with a single isolated long-tracked storm for ease of understanding. Later, I will tackle how this will work with multi-cell storms, line storms, and storms in weak steering flow.

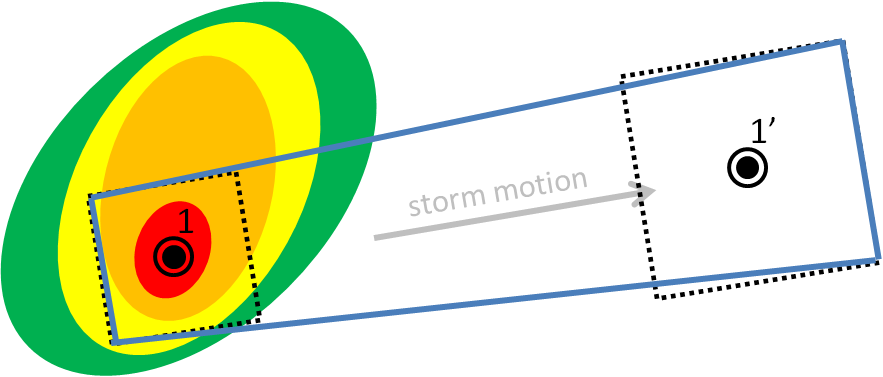

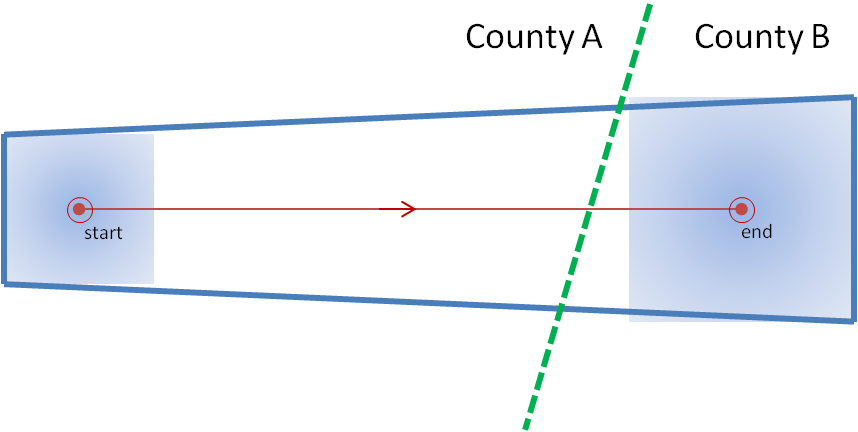

Why are Threats-In-Motion desired? Let’s look at the way most warning polygons are issued today. Threats that last longer than the duration of their first warning polygon will require a subsequent warning(s). Typically, the new warning polygon is issued as the current threat approaches the downstream end of its present polygon or when the present polygon is nearing expiration. This loop illustrates this effect on users at two locations, A and B. Note that only User A is covered by the first warning polygon (#1), even though its location is pretty close to User B’s location. Note too that User A gets a lot of lead time, about 45 minutes in this scenario. When the subsequent warning polygon (#2) is issued, User B is finally warned. However, User B’s lead time is only a few minutes, much less than User A who may only live a few miles away.

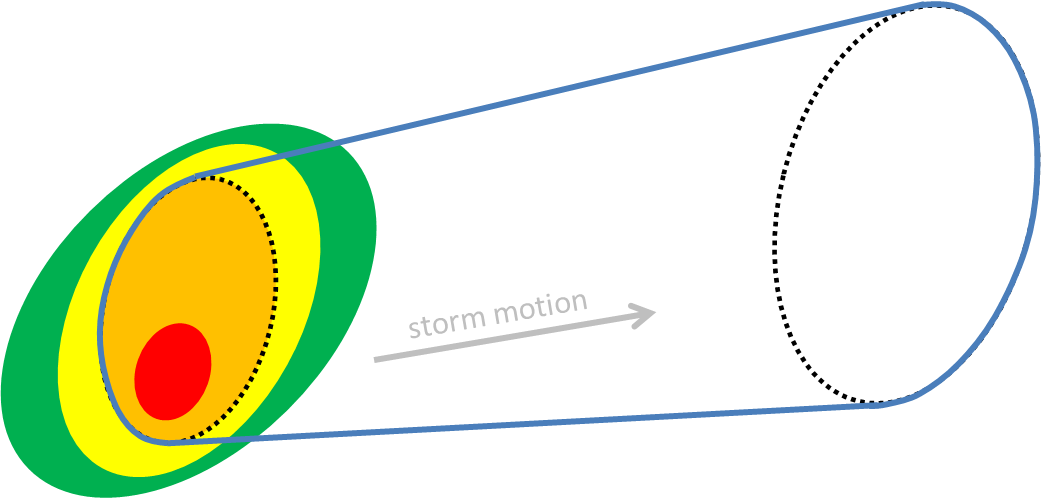

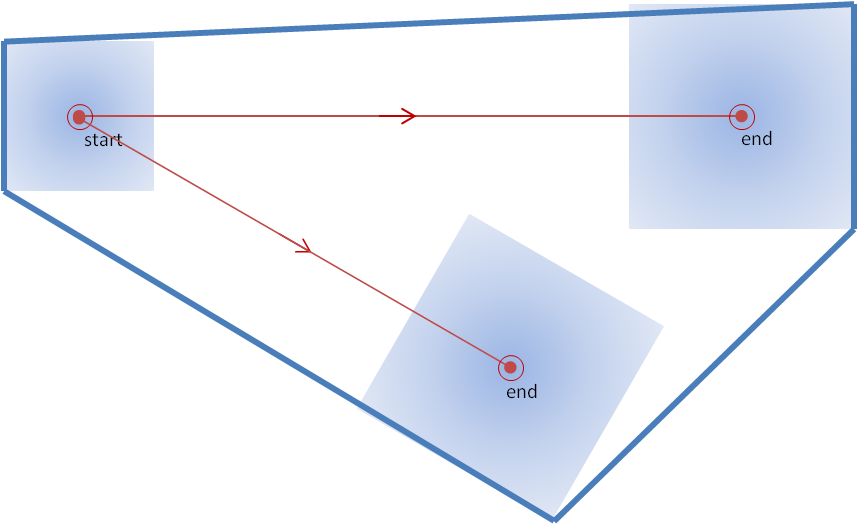

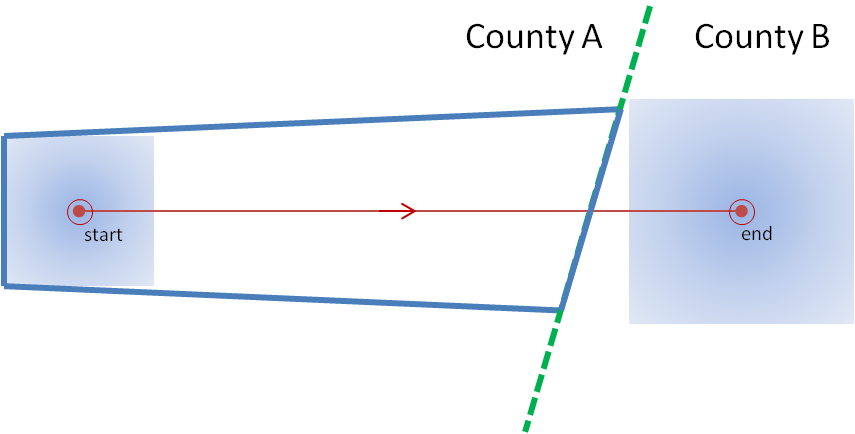

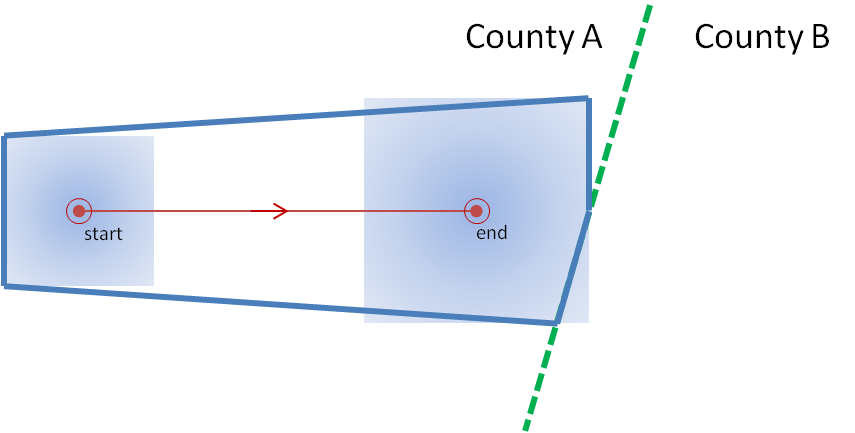

What if a storm changes direction or speed. how are the warnings handled today. Warning polygon areas can be updated via a Severe Weather Statement (SVS), in which new information is conveyed and the polygon might be re-shaped to reflect the updated threat area. This practice is typically used to remove areas from where the threat already passed, thus decreasing departure time. However, NWS protocol disallows the addition of new areas to already-existing warnings. So, if a threat areas moves out its original polygon area, the only recourse is to issue a new warning, sometimes before the original warning has expired. You can see that in this scenario:

Note that a 3rd polygon is probably required at the end of the above loop too!

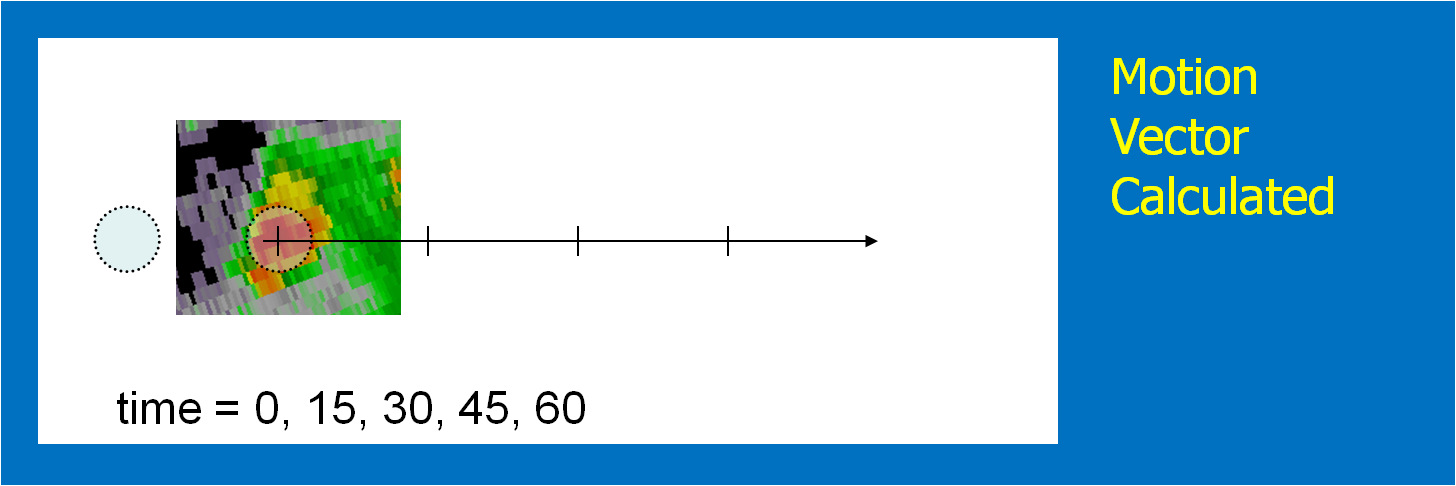

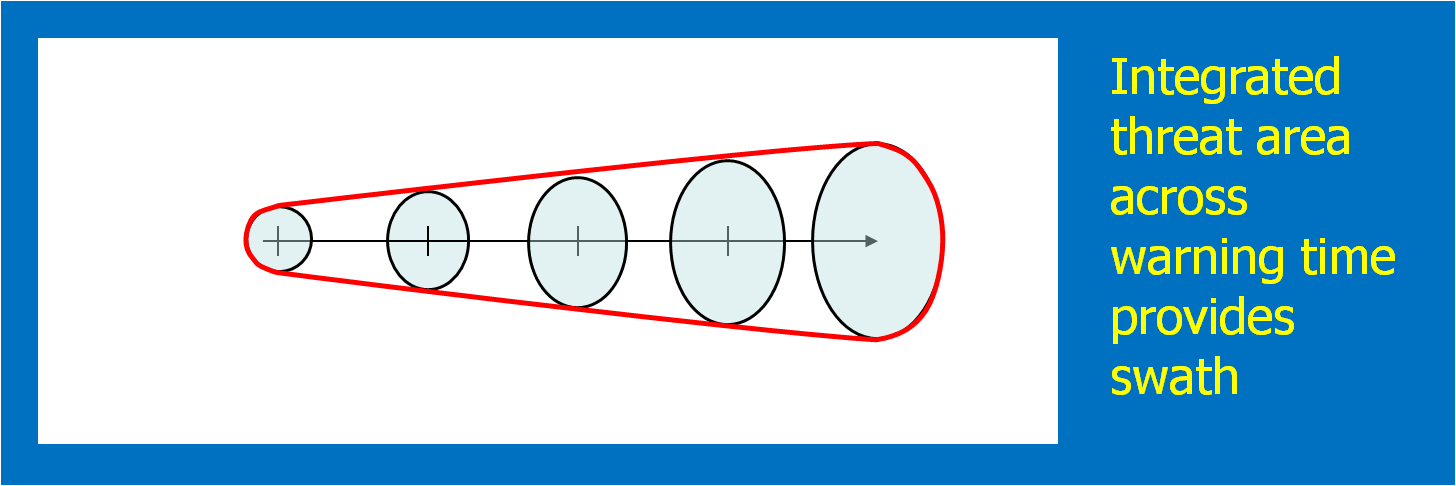

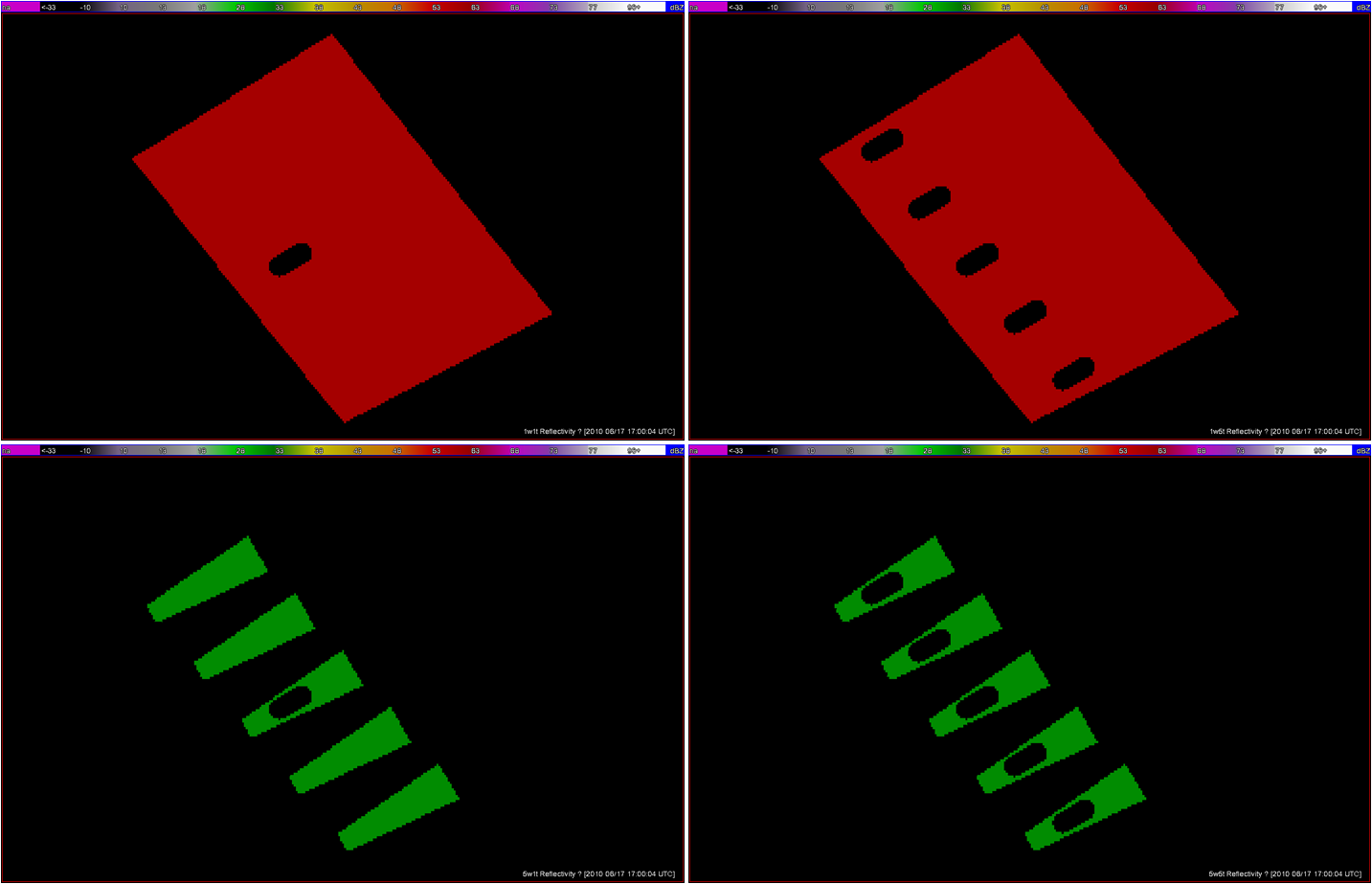

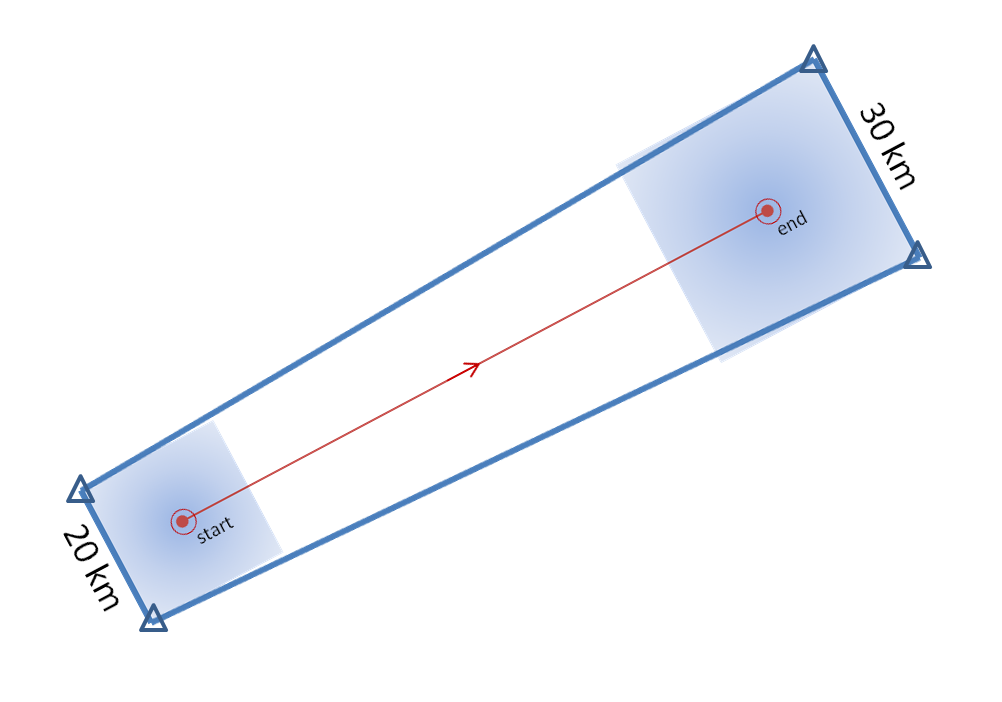

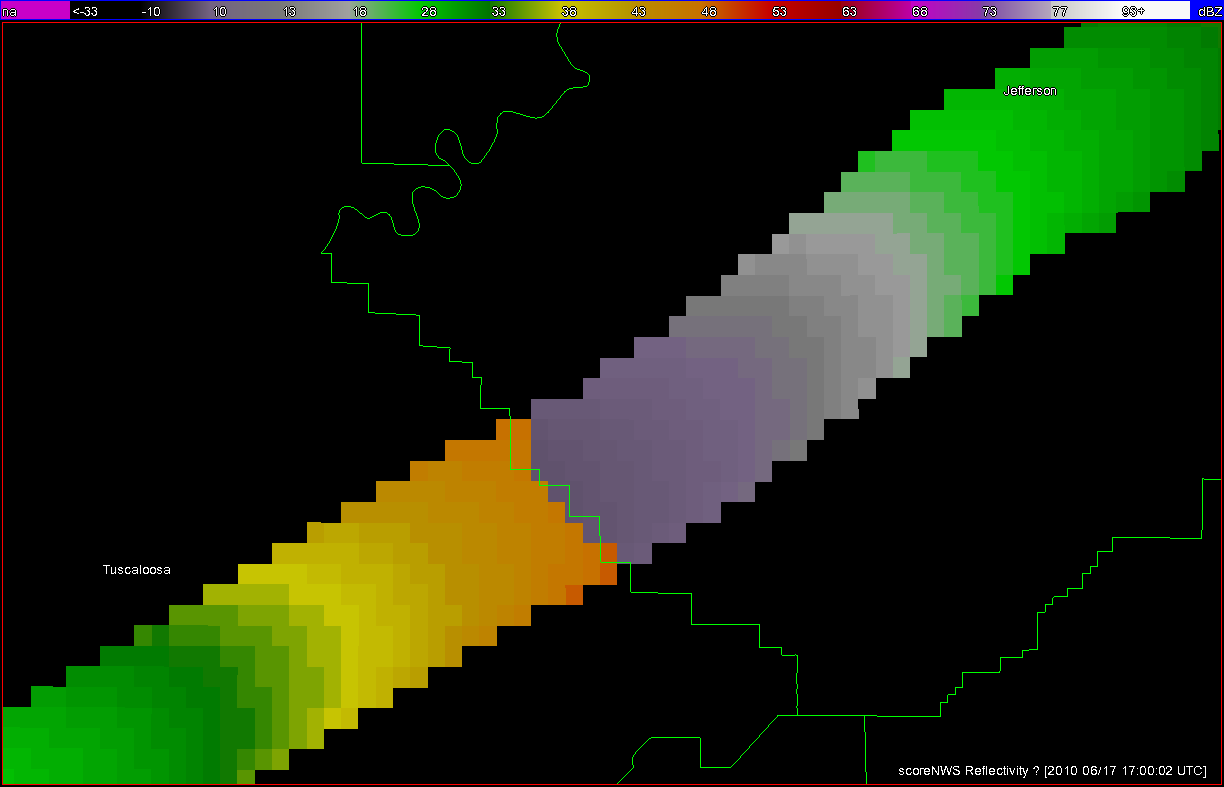

In the past entry, I introduced the notion of initial and intermediate forecasted threat areas. The forecasted areas can update rapidly (one-minute intervals), and the integration of all the forecast areas results in the polygon swath that we are familiar with today’s warnings. But, there is now underlying (digital) data that can be used to provide additional specific information for users. I will treat these in later blogs:

- Meaningful time-of-arrival (TOA) and time-of-departure (TOD) information for each specific location downstream within the swath of the current threat.

- Using the current positions of the forecasted threat areas to compare to actual data at any time to support warning operations management

But what about “Threats-In-Motion” or TIM? Here goes…

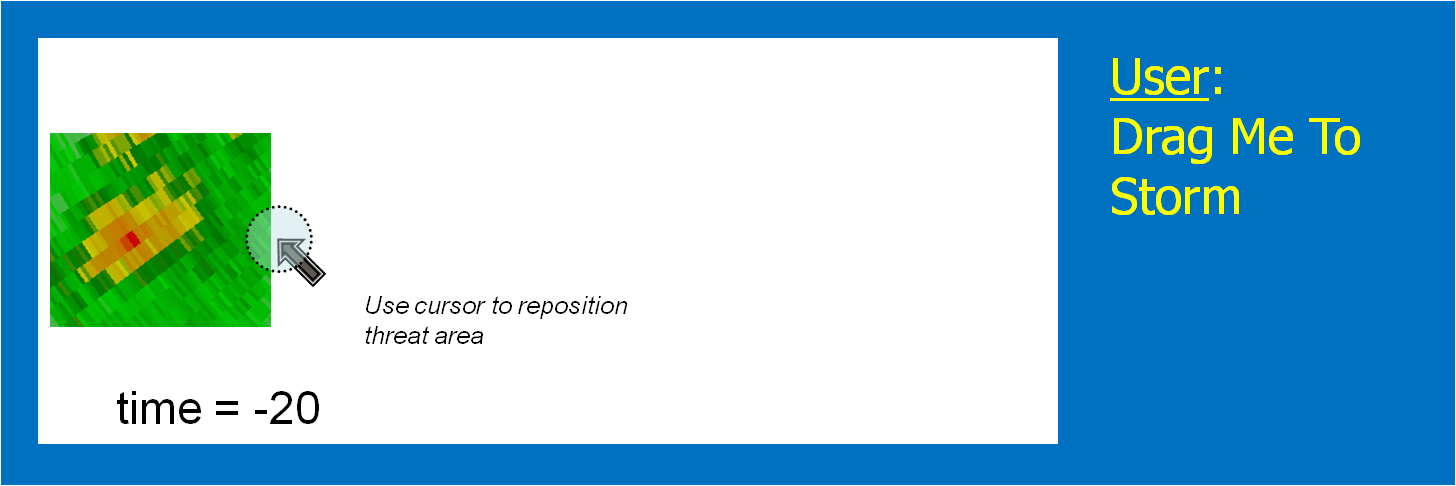

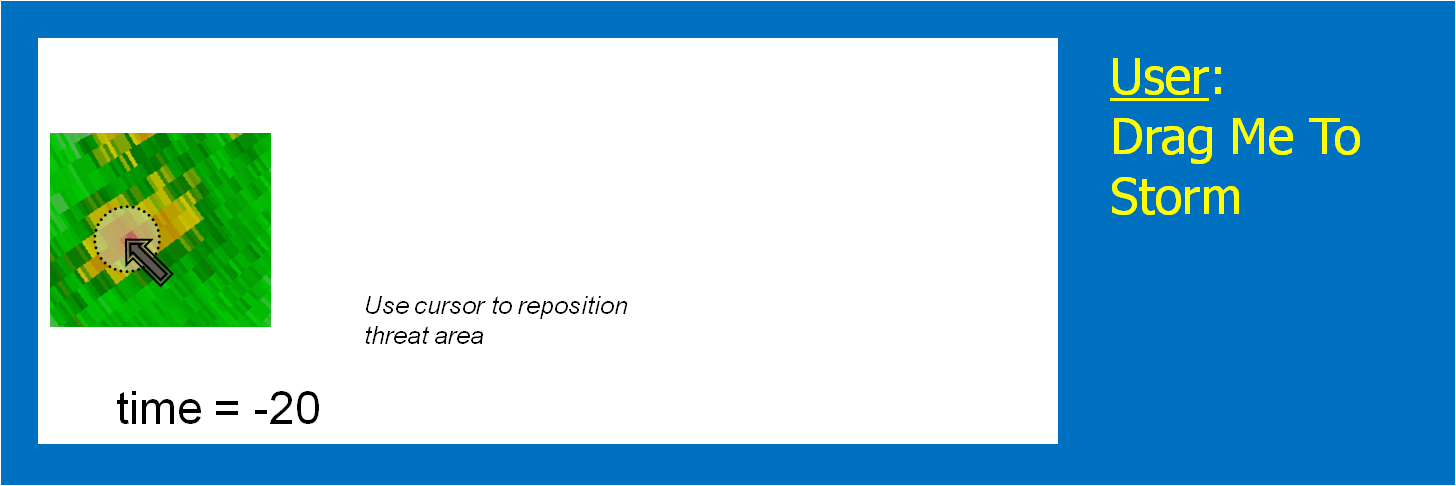

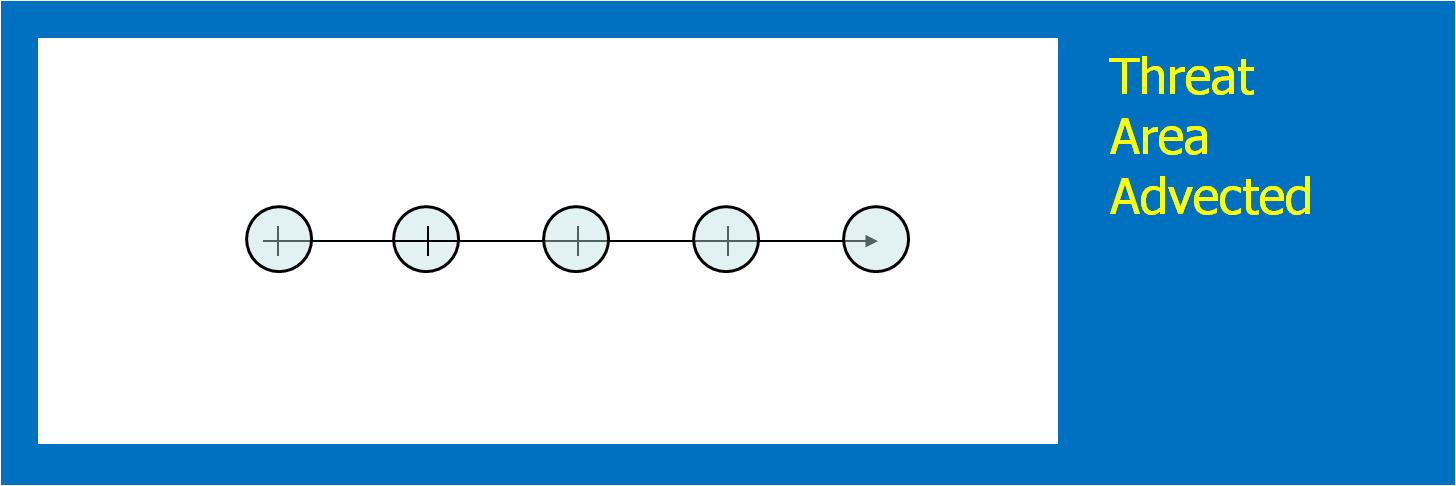

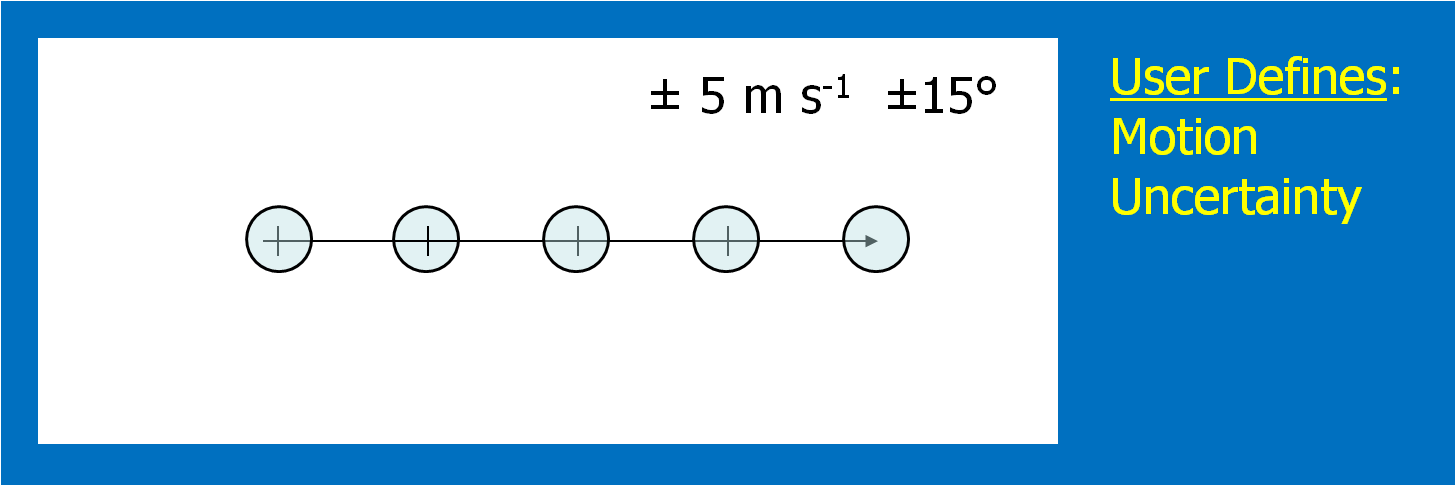

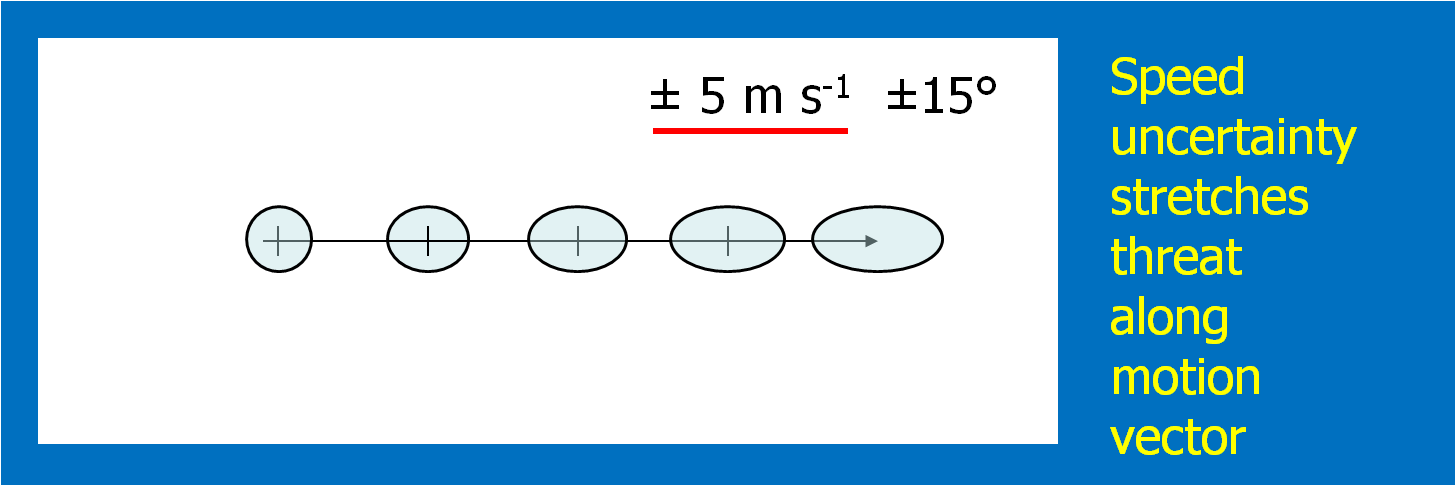

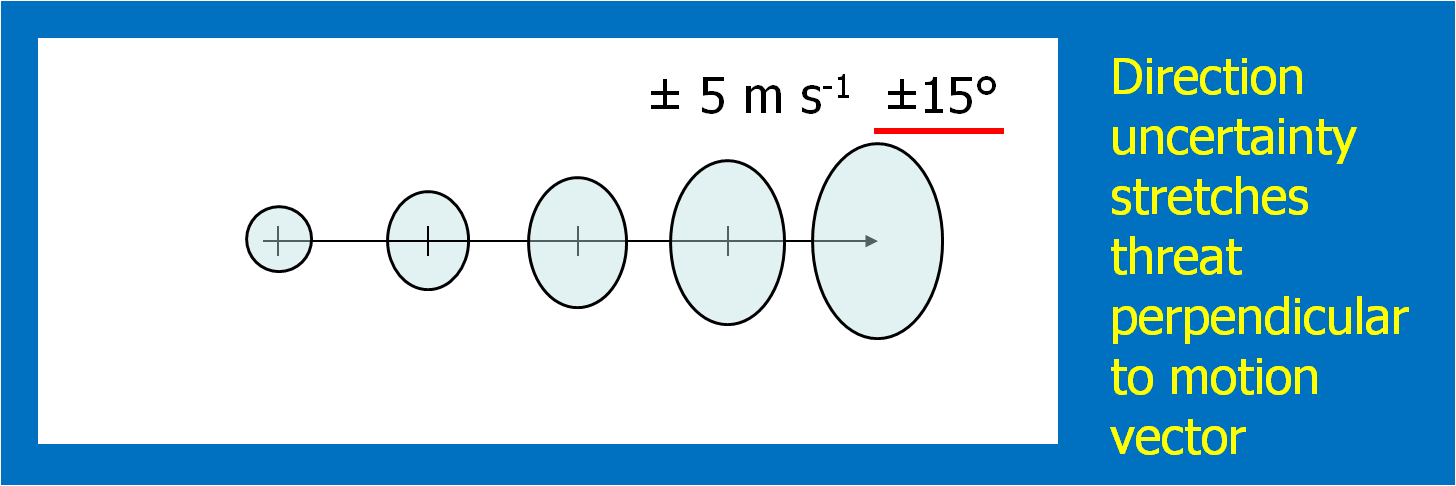

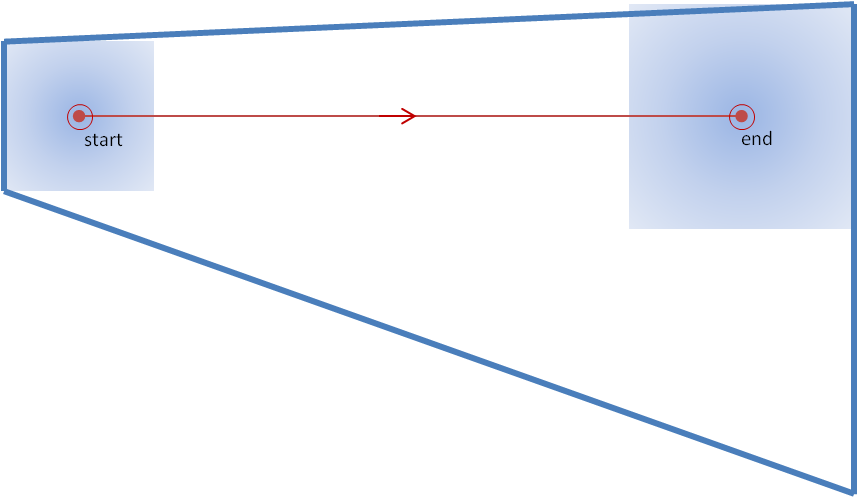

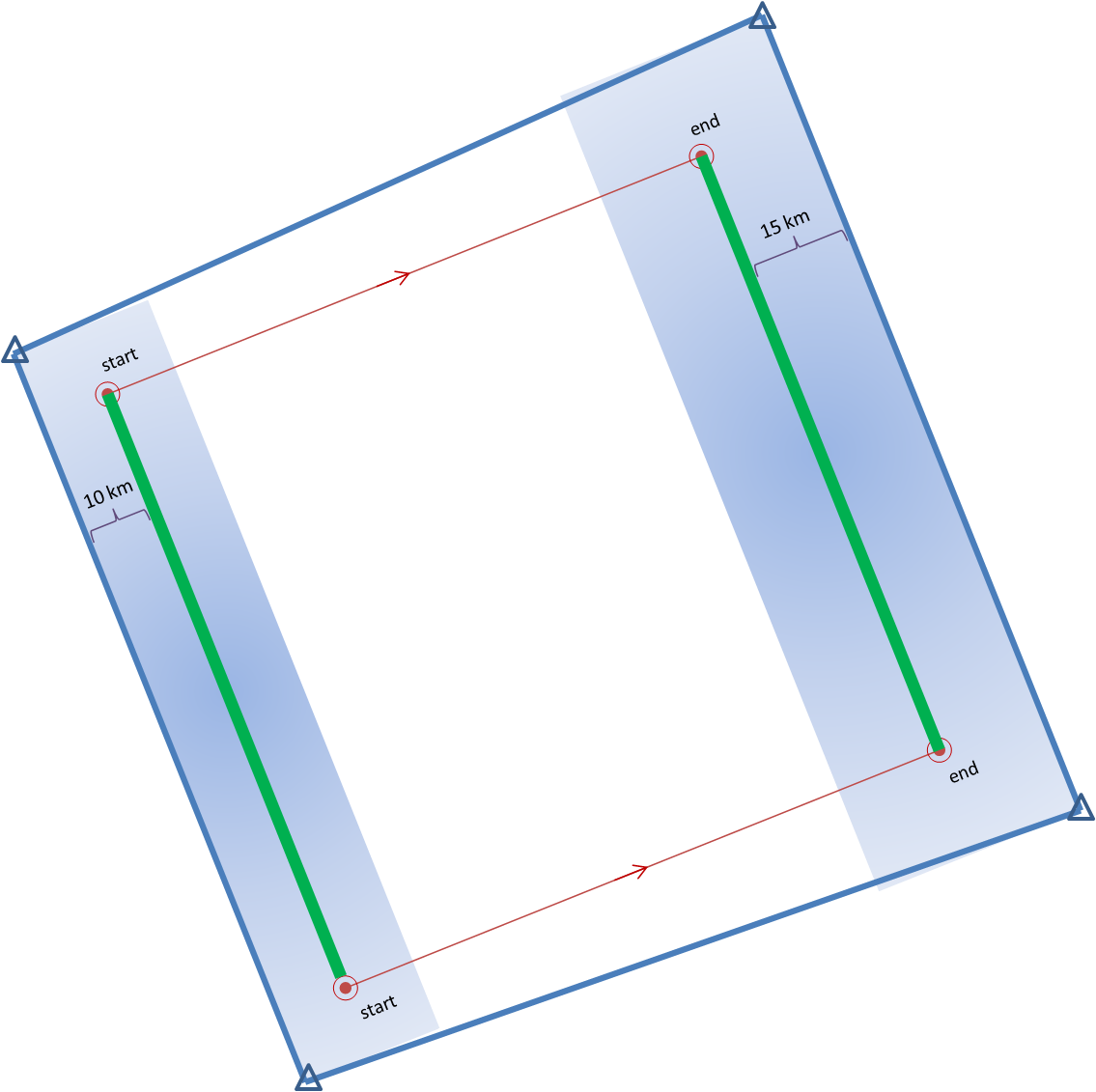

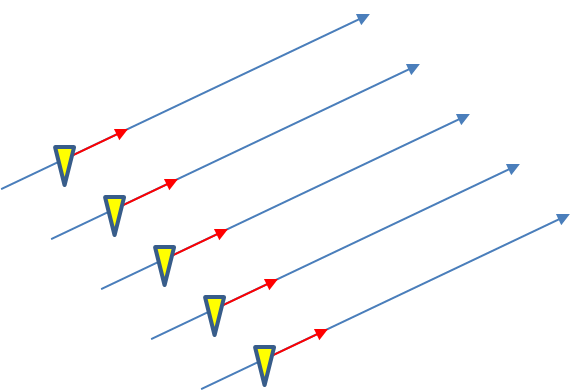

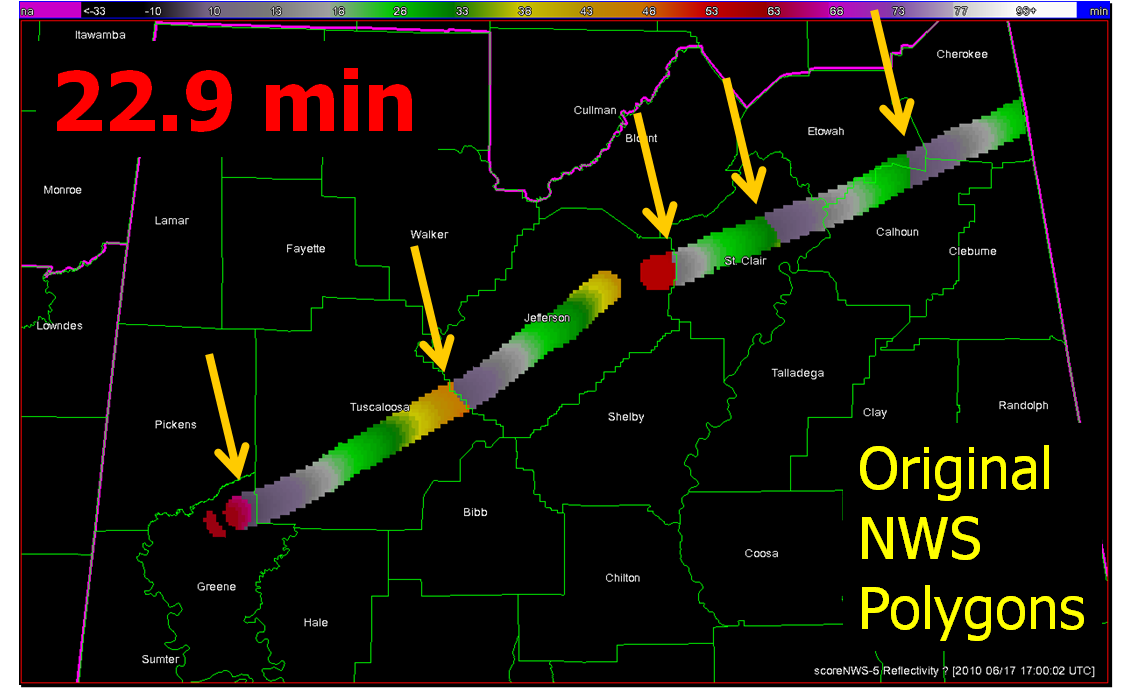

Instead of issuing warning polygons piecemeal, one after another, which leads to inequitable lead and departure times for all locations downstream of the warning, we propose a methodology where the polygon continuously moves with the threat. Our scenario would now look like this:

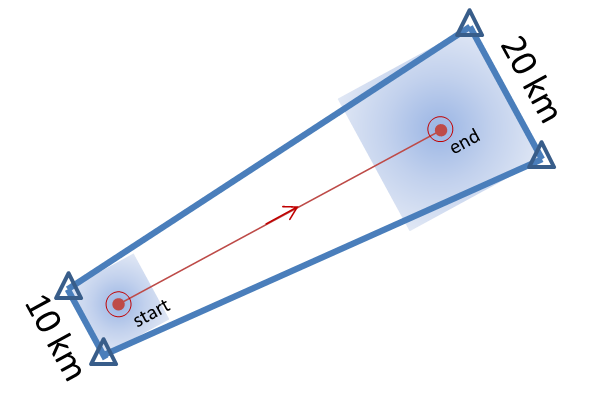

Note that User A and User B get equitable lead time. Also note that the warning area is cleared out continuously behind the threat areas with time. And here is the TIM concept illustrated on the storm that right turned.

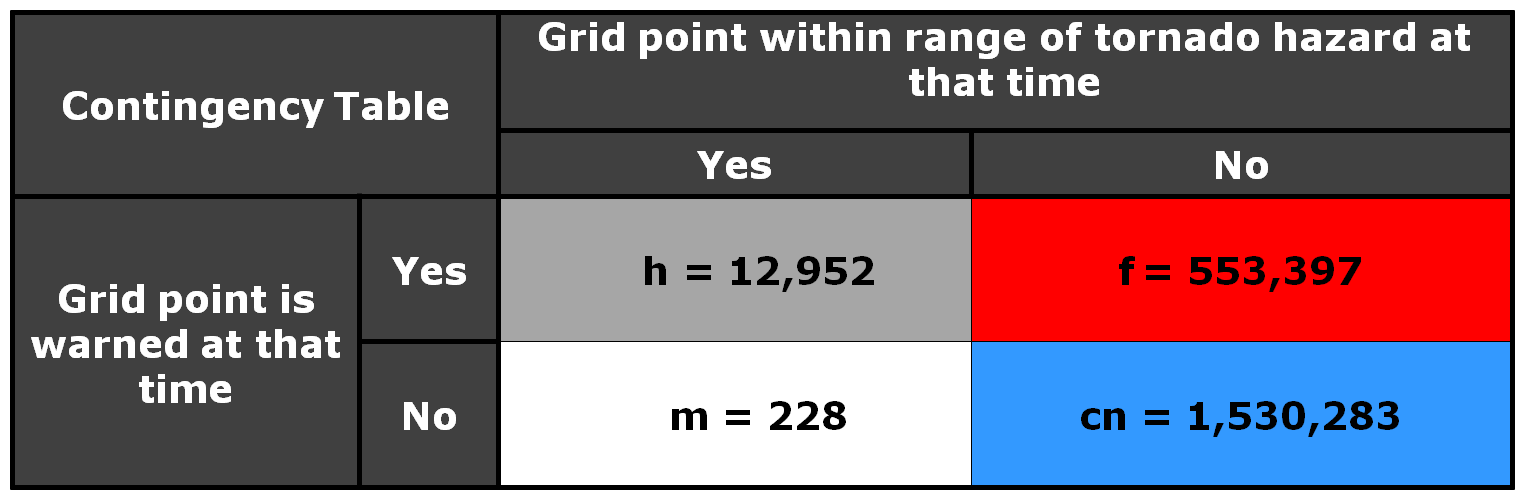

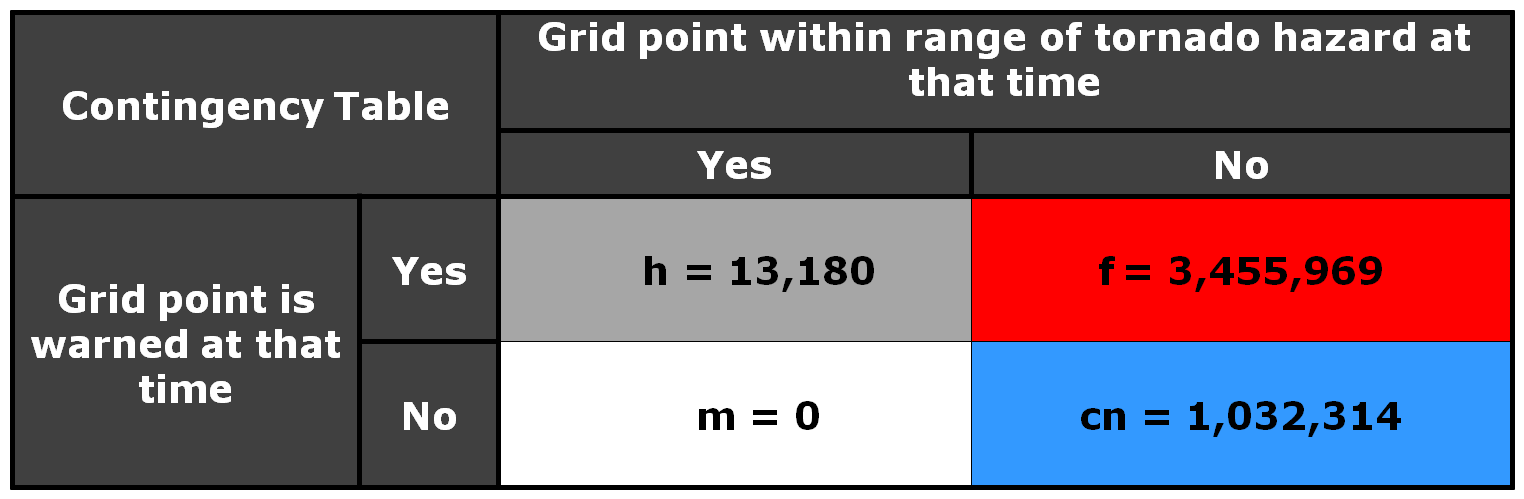

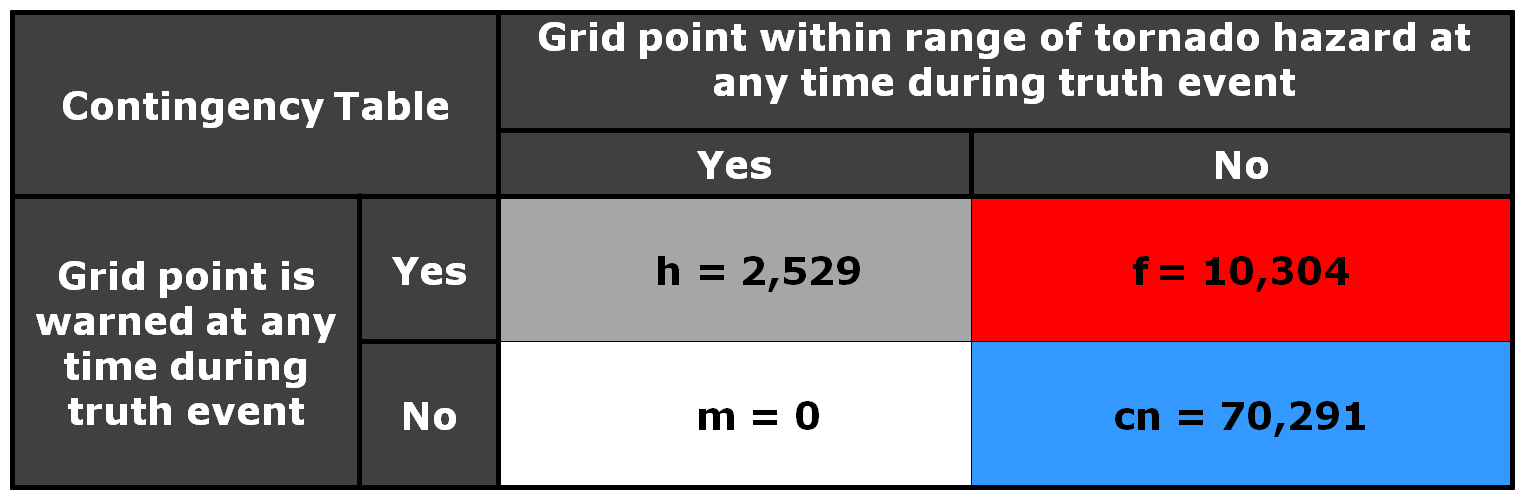

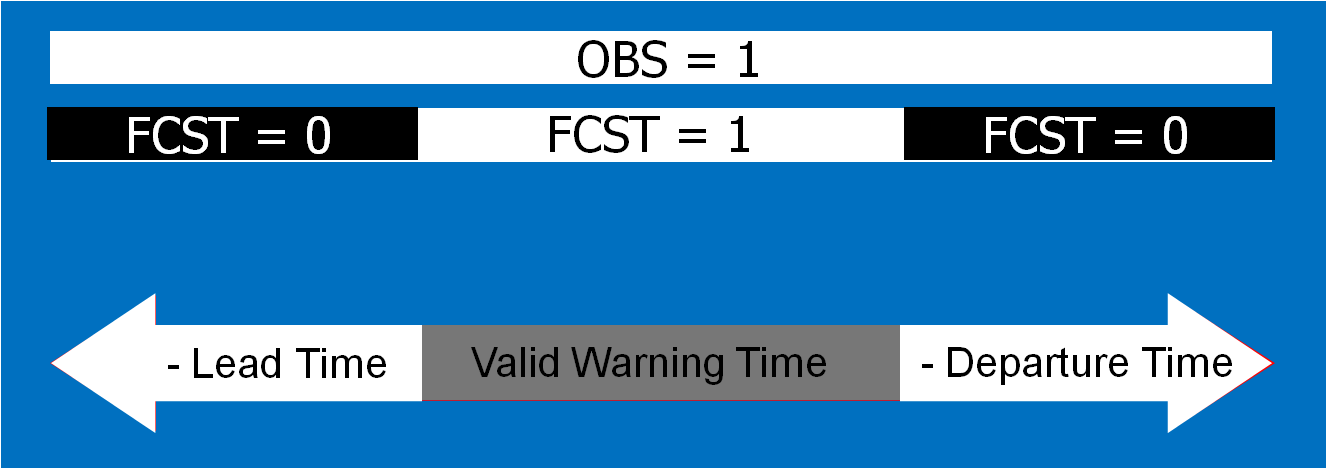

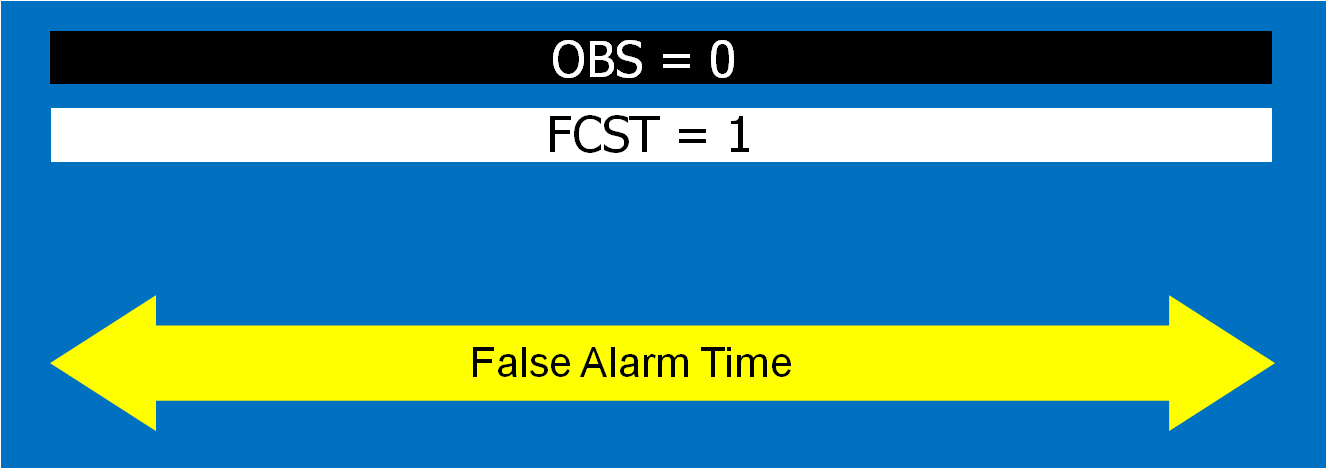

Now let’s test the hypotheses stated at the beginning of this entry. Does TIM improve the lead time and the departure time for all points downstream of the threat? If yes, what about the other verification scores introduced with the geospatial verification system, like POD, FAR, and CSI? The next blog entry will explore that.

Greg Stumpf, CIMMS and NWS/MDL