One of the things that we’re looking at this year in the SFE is forecasting the coverage and the intensity of individual severe hazards – tornadoes, hail, and wind. Ongoing work at SPC has shown that there is some intensity information within the coverage probabilities, and the aim of this aspect of the experiment is to determine how best to unlock that information.

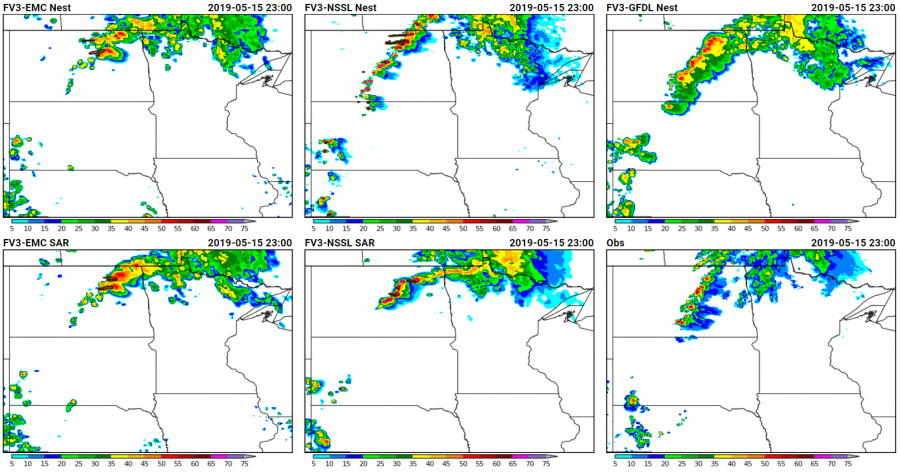

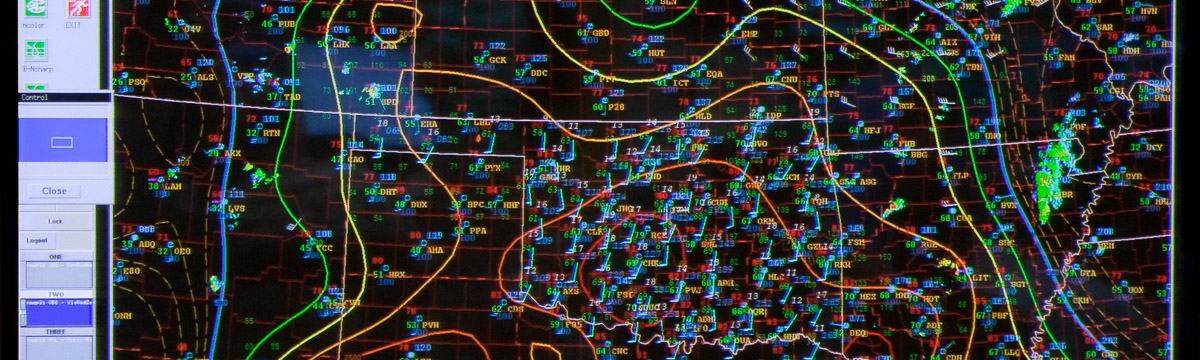

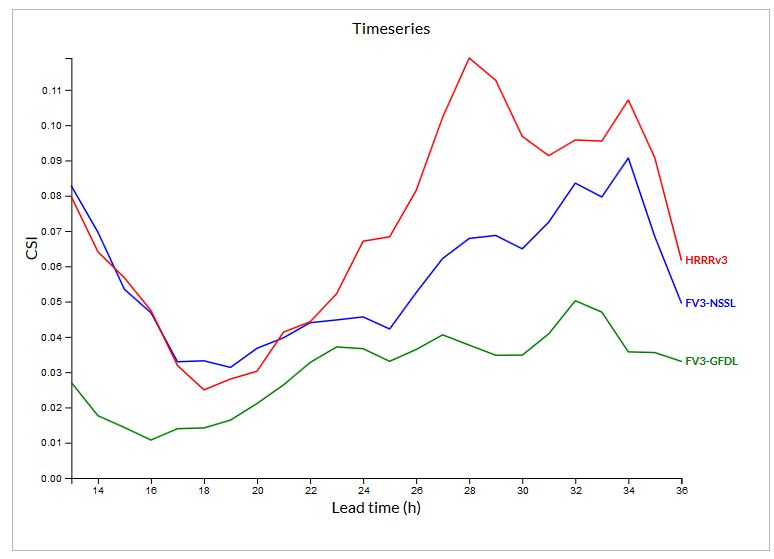

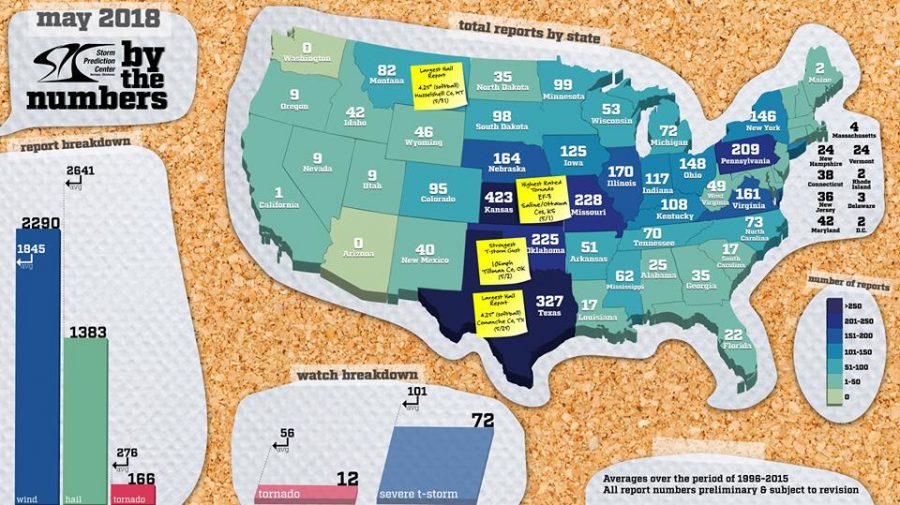

Yesterday, 16 May, provided an interesting case for the conditional intensity forecasts. CAM guidance yesterday was indicating the possibility of rotating, discrete storms across parts of North Dakota, but the location of where CAPE, shear, and the cold front would intersect left questions about the mode of convection and whether or not significant hail would be possible with these given storms. CAM guidance showed the location and progression of the storms quite well, including several experimental FV3-based CAMs that we’re looking at in the experiment.

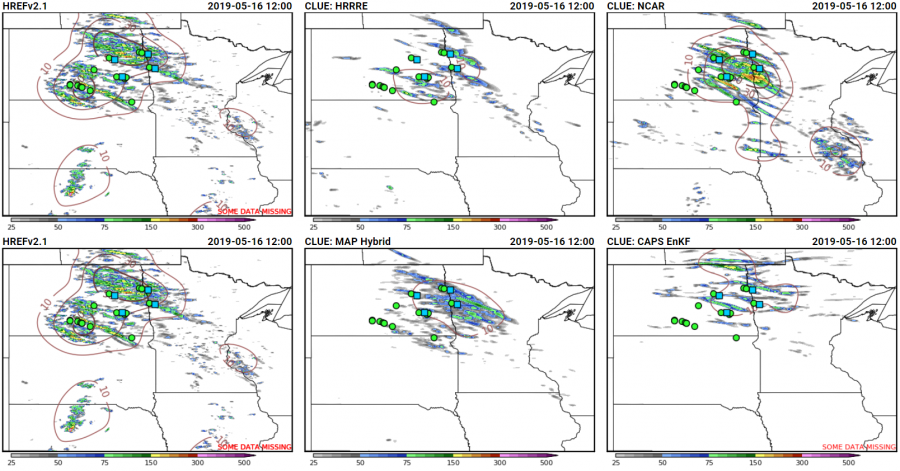

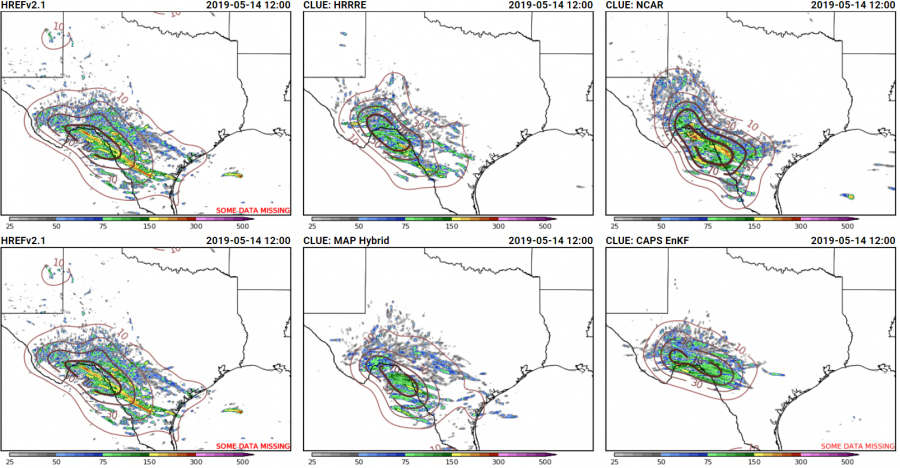

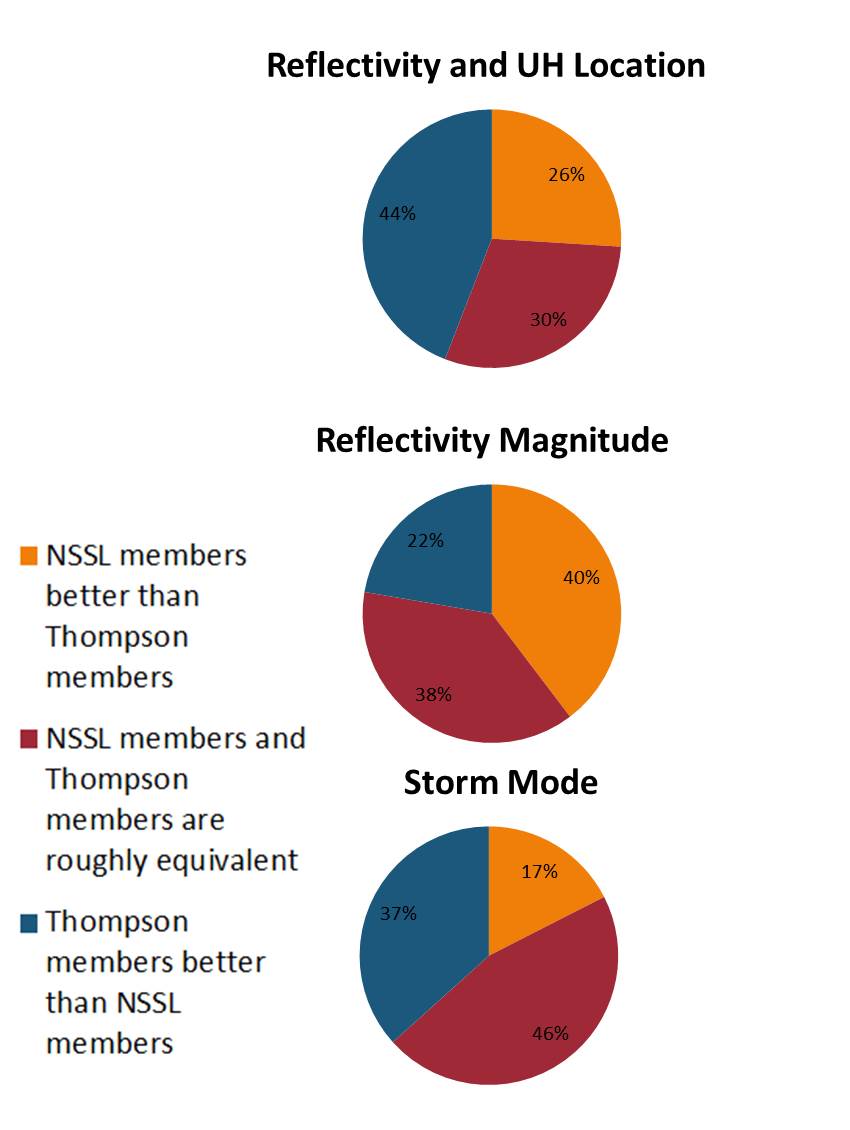

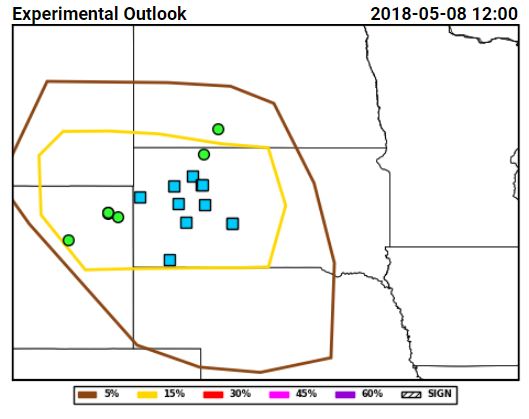

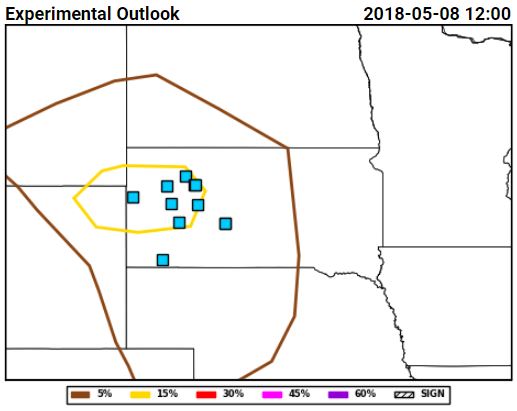

The intensity potential may have been covered better by the ensembles, and showed that a range of outcomes were possible. The 24-h maximum UH fields from several experimental ensembles showed very different depictions of the potential storm severity:

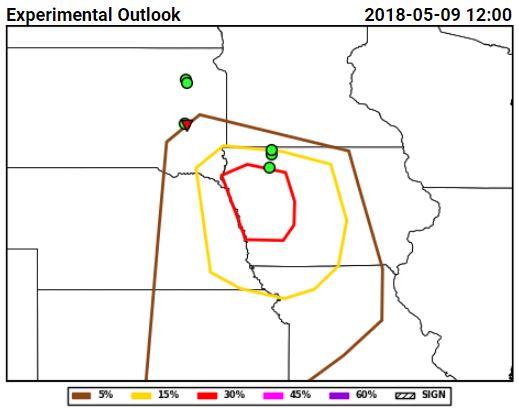

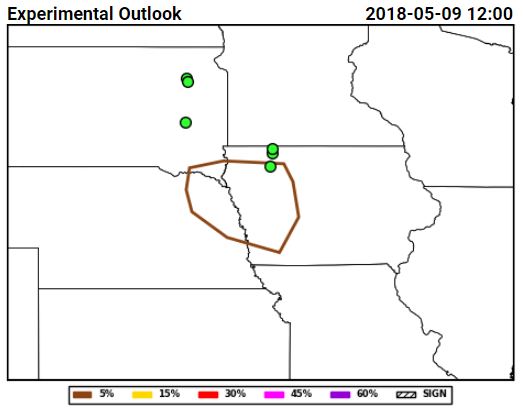

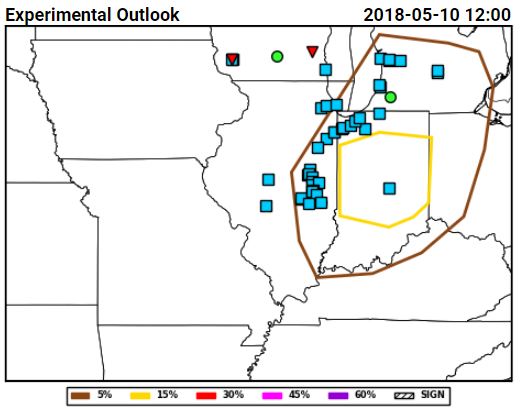

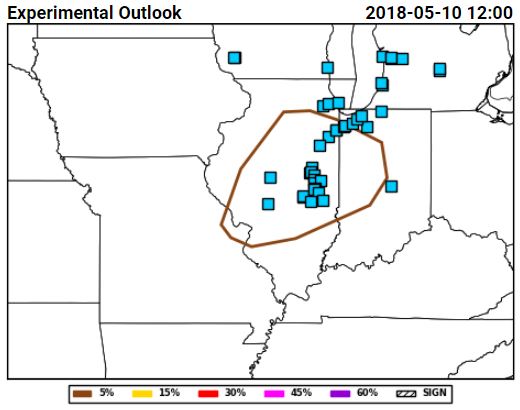

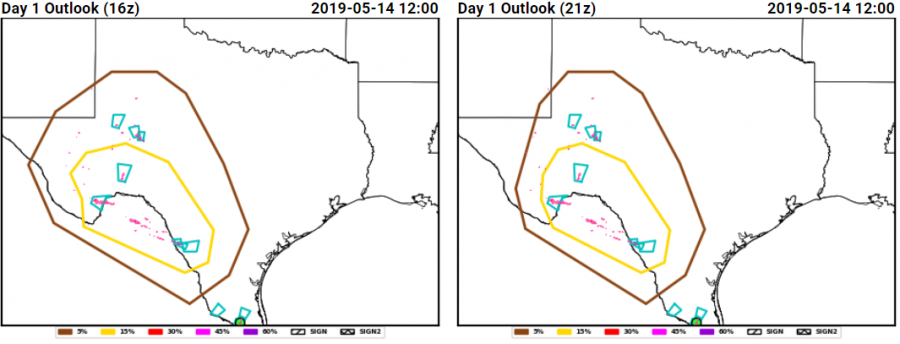

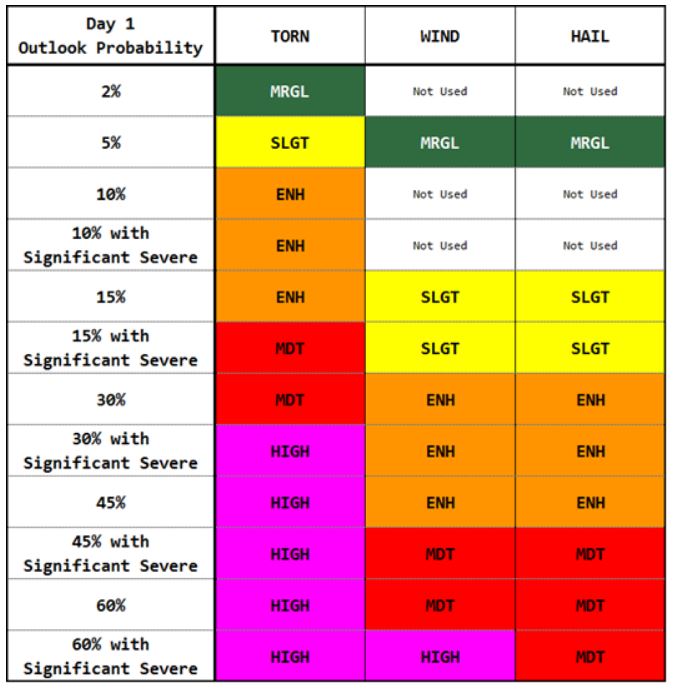

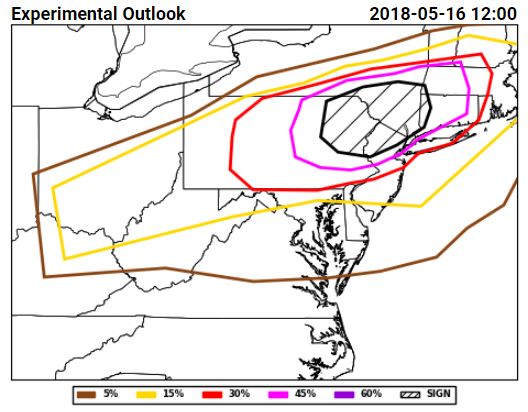

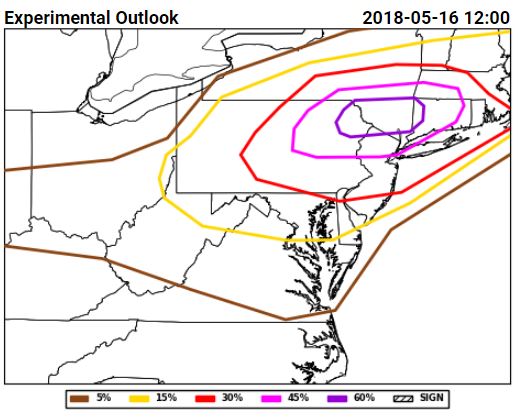

The hail forecasts from the severe hazards desk combined this guidance with environmental analysis information focusing on where the juxtaposition of shear and CAPE would be greatest, and produced probabilistic forecasts that highlighted the area where the largest density of hail forecasts occurred:

This series of forecasts was made (from left to right) the day before the event, the morning of the event, and the afternoon of the event, and shows how the severe hazards desk was able to hone in on the area at risk and reduce the false alarm area, both between Day 2 and the Day 1 outlook issued in the morning, and between the morning and afternoon Day 1 outlooks. Initially, the 15% contour was tailored the most between the Day 2 and Day 1, reducing false alarm across Minnesota. Then, between the initial forecast and the update, the western extent of the probabilities was trimmed as it became evident where the boundary forcing the convection would be.

Additionally, the forecast here not to indicate a threat of significant hail was far from straightforward. Thinking was that storms would remain discrete, especially on the southern end of the line, and could possess rotation. However, we were not confident that the environment could support the production of severe hail, and so decided to forego introducing areas of significant hail. Given the lack of significant hail reports and greater than or equal to 2″ hail in the MESH, this decision was a good one.

This week’s cases have thus far provided interesting challenges, showing differences between CAM behavior in weakly forced situations and with less-than-ideal environmental parameters. Cases like these are critical in understanding how we can best utilize the CAMs to increase forecaster capability in situations where the solutions are far from evident.

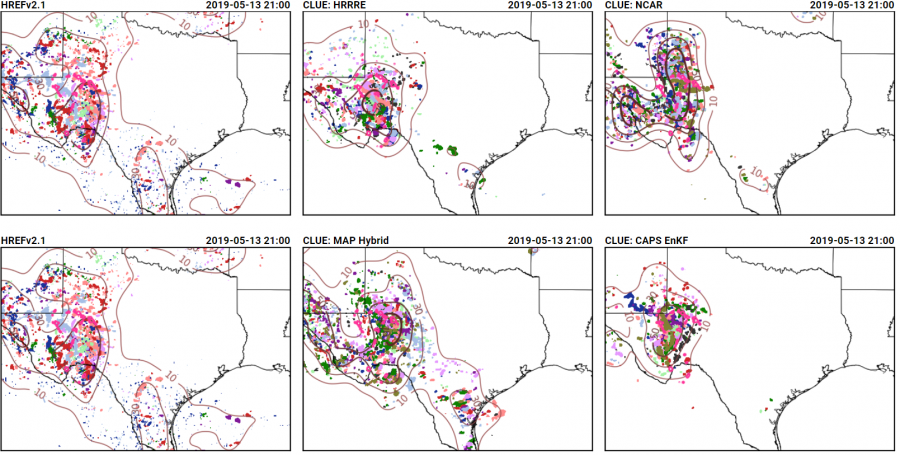

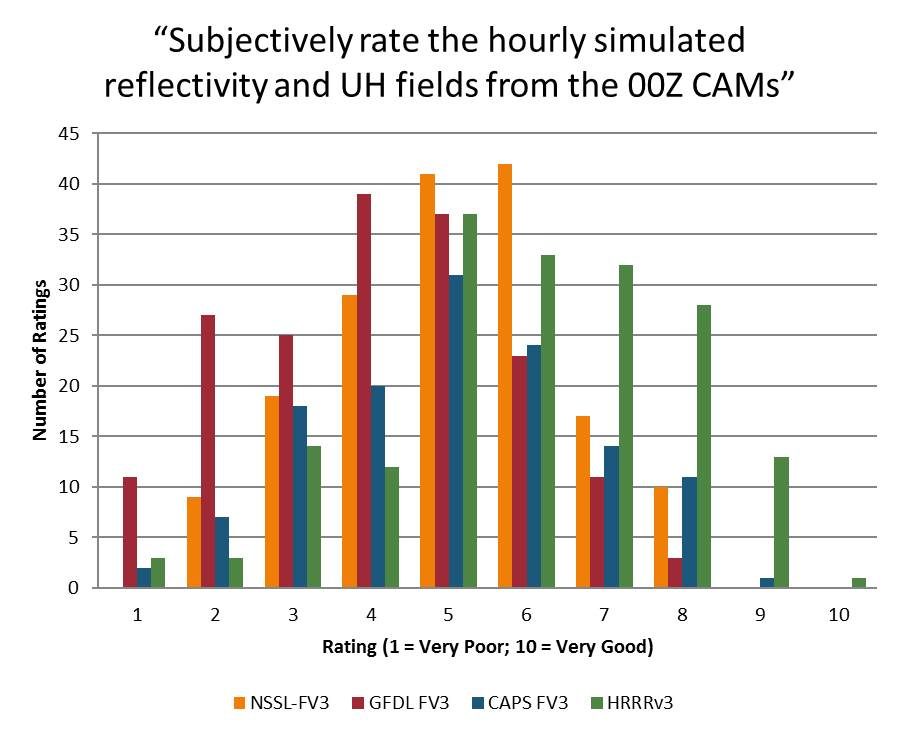

Tuesday for total severe from the Innovation Desk (left) and for hail from the Severe Hazards Desk (right):

Tuesday for total severe from the Innovation Desk (left) and for hail from the Severe Hazards Desk (right):