It is remarkably difficult to predict convection initiation. It appears we can predict, most times (see yesterdays post for a failure), the area under consideration. We have attempted to pick the time period, in 3 hour windows, and have been met with some interesting successes and failures. Today had 2 such examples.

We predicted a time window from 16-19 UTC along the North Carolina/South Carolina/ Tennessee area for terrain induced convection and along the sea breeze front. The terrain induced storms went up around 18 UTC, nearly 2 hours after the model was generating storms. The sea breeze did not initiate storms, but further inland in central South Carolina there was one lone storm.

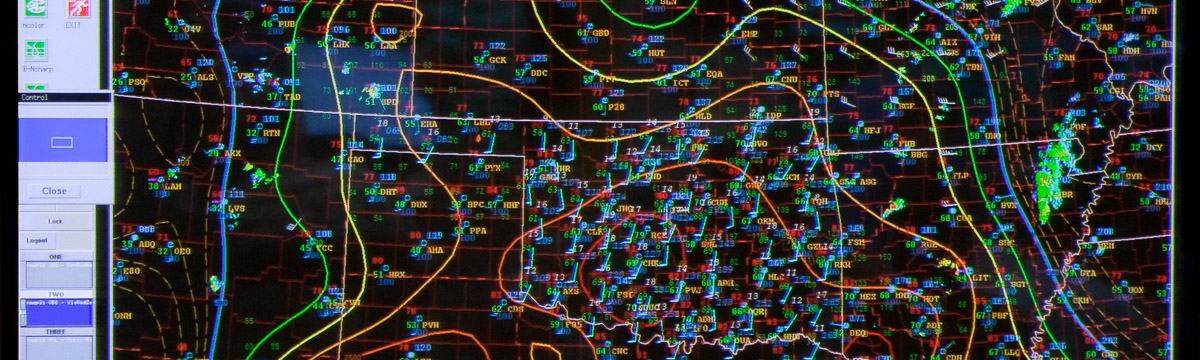

The other area was in South Dakota/North Dakota/Nebraska for storms long the cold front and dryline. We picked a window between 21-00 UTC. It appears storms initiated right around 00 UTC in South Dakota but little activity in North Dakota as the dryline surged into our risk area. Again the suite of models had suggested quick initiation starting in the 21-22 UTC time frame, including the update models.

In both cases we could isolate the areas reasonably well. We even understood the mechanisms by which convection would initiate, including the dryline, the transition zone, and the where the edge of the deeper moisture resided in the Dakotas. For the Carolinas we knew the terrain would be a favored location for elevated heating in the moist air mass along a weak, old frontal zone. We knew the sea breeze could be weak in terms of convergence, and we knew that only a few storms would potentially develop. What we could not adequately do, was predict the timing of the lid removal associated with the forcing mechanisms.

It is often observed in soundings that the lid is removed via surface heating and moistening, via cooling aloft, or both processes. It is also reasonable to suspect that low level lifting could be aiding in cooling aloft (as opposed to cold advection). Without observations along such boundaries it is difficult to know what exactly is happening along them, or even to infer that our models correctly depict the process by which the lid is overcome. We have been looking at the ensemble of physics members which vary the boundary layer scheme, but today was the first day we attempted to use them in the forecast process.

It was successful in terms of incorporating them, but as far as achieving understanding, that will have to come later. It is clear that understanding the various structures we see, and relating them to the times of storm initiations will be a worthwhile effort. Whether this will be helpful to forecasting, even in hindsight, is still unknown.