Each emergency manager (EM) that has participated in our experiment has come with a unique lens through which they viewed and evaluated the experimental PHI. Consequently, multiple themes and sub-themes emerged when discussing EMs’ preferences for and thoughts about PHI during focus groups. For this analysis, the Friday (end-of-week) EM-only focus group discussions from the 2018 Spring Experiment (2 weeks), 2019 Spring Experiment (2 weeks), and 2019 Hazard Services PHI Experiment (2 weeks) were qualitatively coded for themes regarding probabilistic hazard information. These discussions included 23 EM perspectives from various jurisdictions and geographic locations.

Some of the major themes that have emerged are: using PHI and benefits of it, the training that will be required, concerns about putting PHI into operations, how to disseminate PHI, and how the public may use PHI. Each of these themes will be discussed in greater detail.

Using PHI and the Benefits

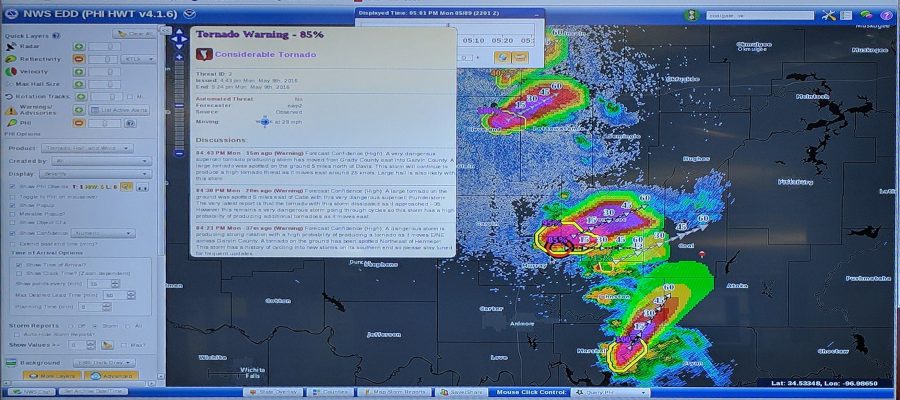

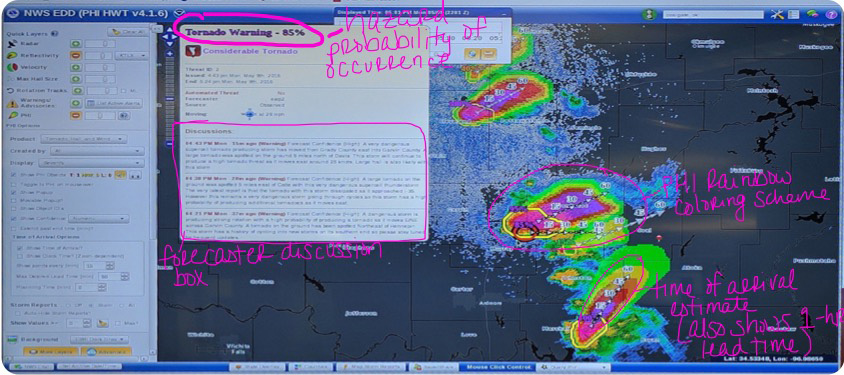

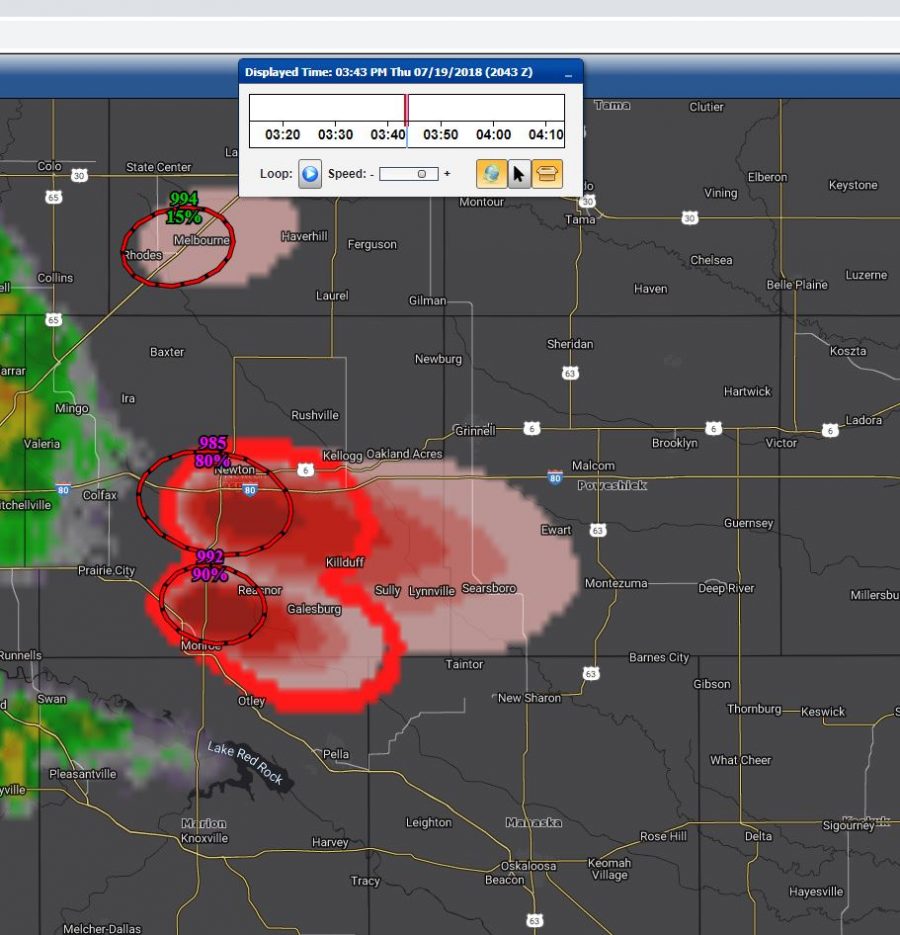

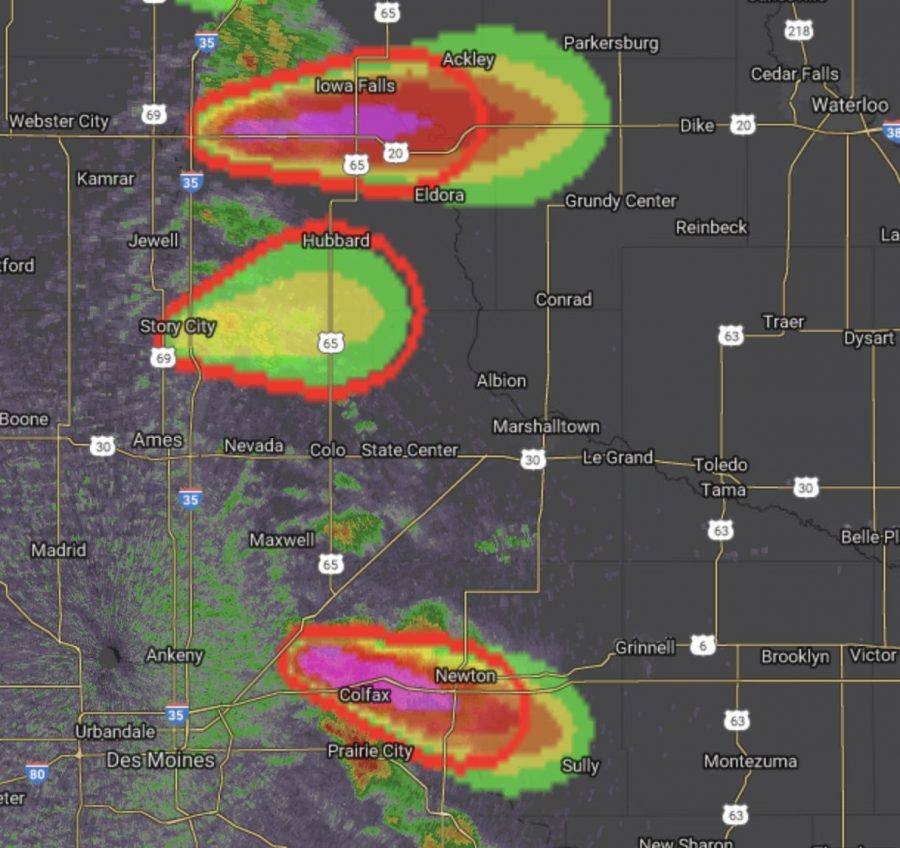

First, EMs had several thoughts about using PHI, including how they would use it and when, the benefits of using it, and their preference for looking at probabilistic information. EMs used PHI in a variety of ways including to maintain overall situational awareness and to monitor storm histories and tracks. Some EMs enjoyed the lightning PHI product because “we just don’t really have anything like that available right now,” while others thought PHI objects were most helpful for tornadoes. Many EMs thought PHI would not be helpful for “garden variety thunderstorms” but some did think PHI could be helpful for a general thunderstorm because, where they live, surprise thunderstorms can “pop up.” They even noted PHI could have worthwhile applications for winter weather and flood events.

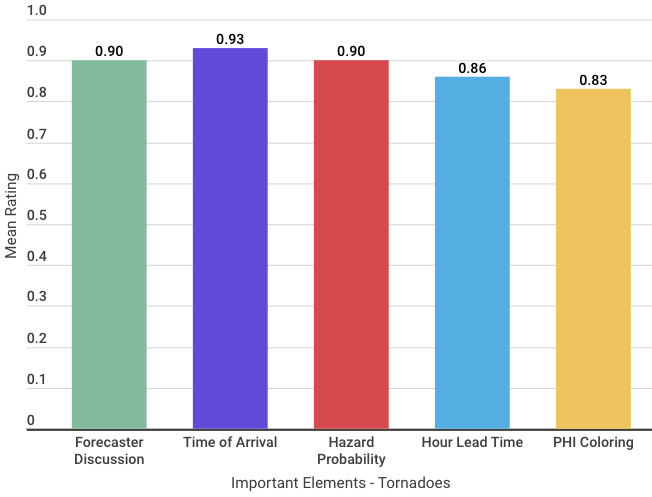

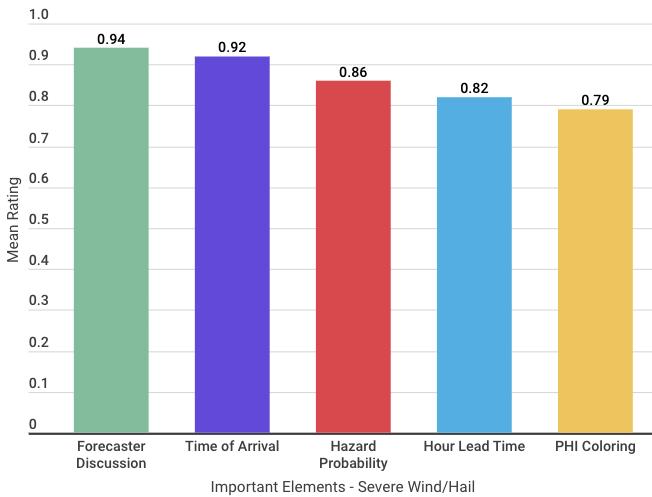

Second, EMs noted many benefits of having PHI as another “tool in their toolbox.” One of the primary benefits of PHI, as noted by EMs, was that it gives them much more information than they currently receive and allows them to anticipate and plan ahead. For example, “you’re talking about…being able to cancel or not cancel something that, if you didn’t have the tool, you would cancel…and you really didn’t have to; you didn’t know there was no need to [cancel].” Many EMs noted the benefit of PHI for event planning; PHI gave EMs a heads up on storm timing, anticipated location, and potential impacts and allowed them to plan and make decisions about events and resource planning sooner than normal. Many EMs noted that timing is everything for them and they really liked PHI for the timing information (e.g., time of arrival) it provided that is currently hard to find.

Another often-cited benefit of PHI was the specified location information. One EM described its importance as, “having the PHI with the…more narrowed down location and then the timing on top of it is just important…this clinic might get skipped over, this clinic needs to actually relocate because of a possible tornado…when you talk about moving patients, staff, and visitors and everything that goes into that, or choosing to shelter in place because the risk is too high to actually move, that makes a difference.” Other EMs also noted that the location information offered by PHI helped specifically with deciding whether to cancel/postpone outside events or simply move them inside.

As a whole, EMs enjoyed the flexibility of the PHI for each hazard and being able to customize options in the EDD and hone in on the aspects that they were most interested in, which tended to vary based on jurisdiction. EMs felt more confident in their decisions, indicated they were able to make decisions sooner and more accurately, and felt as though the PHI offered a greater volume of information that they could filter down to what they needed. They enjoyed receiving the probabilities, even if they did not want the public to see these numbers (which will be discussed in greater detail below). One EM noted that the probabilities “emphasize the area of risk a little more than generalized warnings, so you can get a sense of what the meteorologist is thinking.” Another EM noted they like the probabilities more than words because “words are subjective.” Another EM explained that they liked the probabilities, but they still wanted the explanation to go along with it so they could make their own independent judgment. A few EMs agreed with this notion and indicated that they would like a “hybrid” warning, which was described as a combination of the warnings typically issued today coupled with probabilities of occurrence. As one EM put it, “I do think that [I want] traditional warnings to keep that concrete evidence…yes, this is capable of producing a tornado. Take action now. But then back that up with something like the PHI product.”

PHI Training

EMs discussed what types of training would be needed and how to go about implementing mass-training on PHI. Collectively, they expressed the imperative need for formalized, immersive training. Participants noted the importance of exploring the tool and all of its capabilities in their home jurisdictions to get a better, fuller sense of what it could do and how it could be fully leveraged; something that the artificiality of a simulated experiment cannot provide. They also acknowledged that the one-day training during the experiment was not enough; as one EM noted, it was nice to get a “little bit of time before each [experiment] day [to] get your feet wet…but that doesn’t make you proficient.” Participants did not offer an estimate of the amount of training time they would need to feel “proficient” in using PHI, but several emphasized that refresher training would need to be available as well because “if you don’t use it all day, you will absolutely forget how to use it!” There were suggestions to host training through the OK-First program, some sort of an online platform, or even regional workshops at NWS Weather Forecast Offices (WFOs). Regardless of format, EMs were clear that training needs to encompass both how to use the system (EDD, or whatever platform PHI is hosted on) and how to interpret the PHI probabilities and trends.

Concerns with Moving PHI into Operations

EMs expressed several concerns with PHI moving into operations that were centered around potential misunderstandings, misperceptions, or different interpretations of what the probabilities mean between all groups involved—forecasters, other EMs, and the public and partners. First, EMs were concerned with different interpretations of forecasters’ intentions with probabilities. They would frequently ask, “how do you know what it means to the forecaster?” and “ what does it mean when the probabilities fluctuate?” A similar concern was where to “draw the line” in the probabilities for warnings and “action vs. no action.” These questions led to heavy reliance on the forecaster discussion box, which allowed the forecaster issuing PHI to communicate their thoughts on the storm, a feature that many EMs loved because it provided additional context they were looking for.

A second concern that was voiced concerned different decision thresholds across EMs in response to similar PHI. As an example, many EMs noted what “50%” means to one person may not mean the same thing to the next person, which may lead to differential decisions. As one EM stated, “I didn’t make the decision (sound the sirens) even though it was at 50% and then the next time I did make the decision based on 50%. So how do you figure that out?”

Another concern voiced was whether PHI would confuse the public and partners. Many EMs were concerned that it would be too much; EMs indicated that they wanted it for themselves but worried that the public would not understand it. One aspect EMs specifically pointed out as worrisome for the public was the 2-minute update period; EMs thought that rapid update time might be confusing for some people as they may not fully understand the trending or fluctuating probabilities. EMs were also worried that, as a product of not fully understanding the information, people may take less action in response to it. As one EM said, “we have to consider how the public would receive this,” while another EM said, “we may overestimate the public’s ability to take action with a lot of information,” a third EM said, “I think you could easily overwhelm and confuse them.” Ultimately, more work with the public is needed to better understand their capacity to understand PHI and use it effectively for informed decision-making.

Lastly, EMs were concerned about shifting from a binary warning system to a warning system built on a probabilistic continuum. Many EMs noted they liked the current binary system for its ease of understanding: either you are in a warning or you are not. However, shifting to probabilistic forecasts provides people with a “continuum to determine their own risk level and whether or not they should take action. So we may lose a lot of people taking action.” Thus, this EM recommended that while there may be a continuum of risk, the product for the public “needs to be more definite.” Similarly, another EM noted that the binary system creates “two levels of decisions” whereas with probabilities, “you’ve got ten.”

All in all, there have been many concerns that center on consistency of interpretations and understanding of the product. While EMs still very much want this information for themselves, they are leery of providing it to others in its current numeric form. However, EMs noted some hope that these concerns could be addressed by adequate training.

Disseminating PHI to the Public and Partners

Fourth, while EMs might be hesitant to make this instantly available to the public for consumption, they did discuss mechanisms through which PHI should be disseminated and what should be included in the messaging to the public and partners. Many EMs suggested social media platforms as venues for delivering PHI in today’s society. Other EMs suggested using pre-existing alert systems that send notifications directly to cell phones. Other EMs suggested the information could be put on a website with links to more detailed information for people who are interested in learning more or seeking additional information.

While thinking about a paradigm where PHI is made public, EMs indicated that PHI should not come from them; they would be happy to pass PHI along but they felt strongly that it should originate from NWS. They thought the information would be more official and more trusted if it came directly from NWS. “It needs to be discussed with NWS and we need to follow that because they are the ones who are putting this out and we are just passing on the information,” and, “there still has to be a message to the public that should not be filtered through us. We can relay messages and that sort of stuff and so can the broadcast media, but ultimately when the NWS issues that PHI plume, that’s going to mean something.”

EMs also remarked on what should be included in public messaging. Some EMs noted that specificity is critical. Other EMs noted that impact should be included. Another EM suggested the information should be formatted as bullet points instead of summary text. Many EMs agreed that messaging, in whatever form it is delivered, should be concrete and definitive; “gray” or uncertain information should not be sent out. In particular, an EM said, “there’s a bit of anxiety from an emergency manager about providing them too much gray.” EMs also stressed making the information personalizable; Zulu or UTC times should be eliminated in favor of local times, and location information is essential and should be provided when possible. EMs thought this would help make the information more easily digestible for the average person.

Regardless of what gets conveyed to the public and how it gets sent out, EMs were in consensus that they did not want the public-at-large to have to interpret PHI on their own and make their own decisions. They were collectively worried about that leading to a decrease in the number of people taking appropriate protective actions when needed.

Opposing thoughts on the Public’s Use of PHI

Lastly, some emergency managers thought the public might use PHI. Many EMs suggested that while they really did not want the public to see PHI, they also believed it would become public anyway. “People are going to get this information wherever they are. There’s so many different blogs out there that people do have access…” “Let’s face it, they (the public) see stuff and they get apps and they can look at it…” were comments shared by two EMs but endorsed by many others. Other EMs expressed that they were somewhat okay with making PHI public because they do not believe people will go seeking the information. One EM said, “The public’s not really going to seek out that information unless there’s a reason to.” As another EM put it, “I don’t believe the everyday citizen is going to wake up in the morning and turn on the PHI and see what the weather’s going to be like today.” Another EM also conveyed this point by saying, “I don’t believe the public is going to seek out this information on a daily basis.” Because people may not use this information often, EMs stressed the importance of also having a strong public education campaign on how to use and interpret PHI.

Taken together, not every EM agreed with giving PHI to the public, but many EMs believed that the public would find a way to get the information. Thus, a centralized plan on how this information would be delivered to the public should be developed for consistency and trust in the information.

We have gathered very rich information from participants over the years, and this blog post provides a high-level overview of some key themes that have emerged in the 2018 and 2019 experiments with a particular focus on PHI. Stay tuned for more updates and information about other aspects of the Experiment and other data collected!