This blog describes research carried out recently in OU-CIMMS’ Behavioural Insights Unit (BIU) in an attempt to draw together the wide-ranging literature related to tornado epidemiology. The literature included Centers for Disease Control (CDC) reports, grant reports and NOAA Service Assessments alongside academic journal articles for the first time.

It was recognised that there are gaps in our collective knowledge, due to gaps in records or a series of methodologies that don’t necessarily talk to each other. Undertaking a meta-analysis to better understand the specificities of tornado fatalities, can provide a baseline for understanding the direct causes as much as possible, as well as examining previously overlooked literature was proposed as a method for identifying such gaps.

Meta-analyses often look at large data sets, examining literature from the medical sciences field, calling for a quantitative analytical approach. Such an approach makes an examination of study selection, summarizes measures such as risk ratio, difference in means, among others. However, while undertaking the initial literature searches it became clear that this approach was not suitable here and a new approach might need to be taken. For instance, some studies (e.g. Brooks and Doswell, 2002 and Hammer and Schmidlin 2002), take historical approaches, whereas CDC reports take purely epidemiological approaches, with some contextual information offered in places. Consequently, this variability of included literature lends itself to a more open method of synthesis, using meta-ethnography as an approach.

Meta-ethnography as a method allowed for key themes to rise to the surface. Some of these themes are well known, such as vulnerability of mobile home residents, but the layers of complexity underpinning their vulnerability is also explored by linking this to other so-called ‘vectors of vulnerability’ (defined and discussed below), as a way of showing the levels of complexity that exist when attempting to reduce tornado impacts on communities.

A key finding is that complexity exhibited by these vectors of vulnerability is key to understanding drivers of risk, and how these impact on survivability. There is not one simple solution to reducing risk of fatality because there are multiple vulnerabilities which when coupled with the magnitude of the hazard (provided by the EF scale) all underpin varying degrees of risk that likely impact on survivability of tornadoes.

The key themes that were discovered and analysed are discussed below. The full report is available here or by clicking on the image below (Note this will open in a new browser window).

Theme One: Contextual Epidemiology

The theme of contextual epidemiology brought insights into where victims were, what protective action they took, how effective it was/was not and if they received a tornado warning in enough time to react appropriately. Contextual information across the literature included in this study, included details on how much of the housing structure was destroyed and whether this was seen to be a vector of vulnerability in terms of driving higher fatality numbers.

Other contextual information related to warning lead times, as well as whether victims were able to take sheltering action, what this was and its effectiveness. The two emerging themes from this data, ‘housing structure’ and ‘warnings’ are both complex vectors of vulnerability.

Of note, CDC reports or NOAA Service Assessments are only carried out for large scale or high fatality events. This means that potentially there is data not being recorded adequately or with enough context to make accurate analysis of risk, vulnerability and specific causes of fatalities. Epidemiology studies and investigations that were undertaken, are able to be included in analyses such as this, allowing contextual epidemiological information that contributes to a broader pattern of understanding of the multiple risks that are likely to derived from vectors of vulnerability, described below.

Theme Two: Vector of Vulnerability

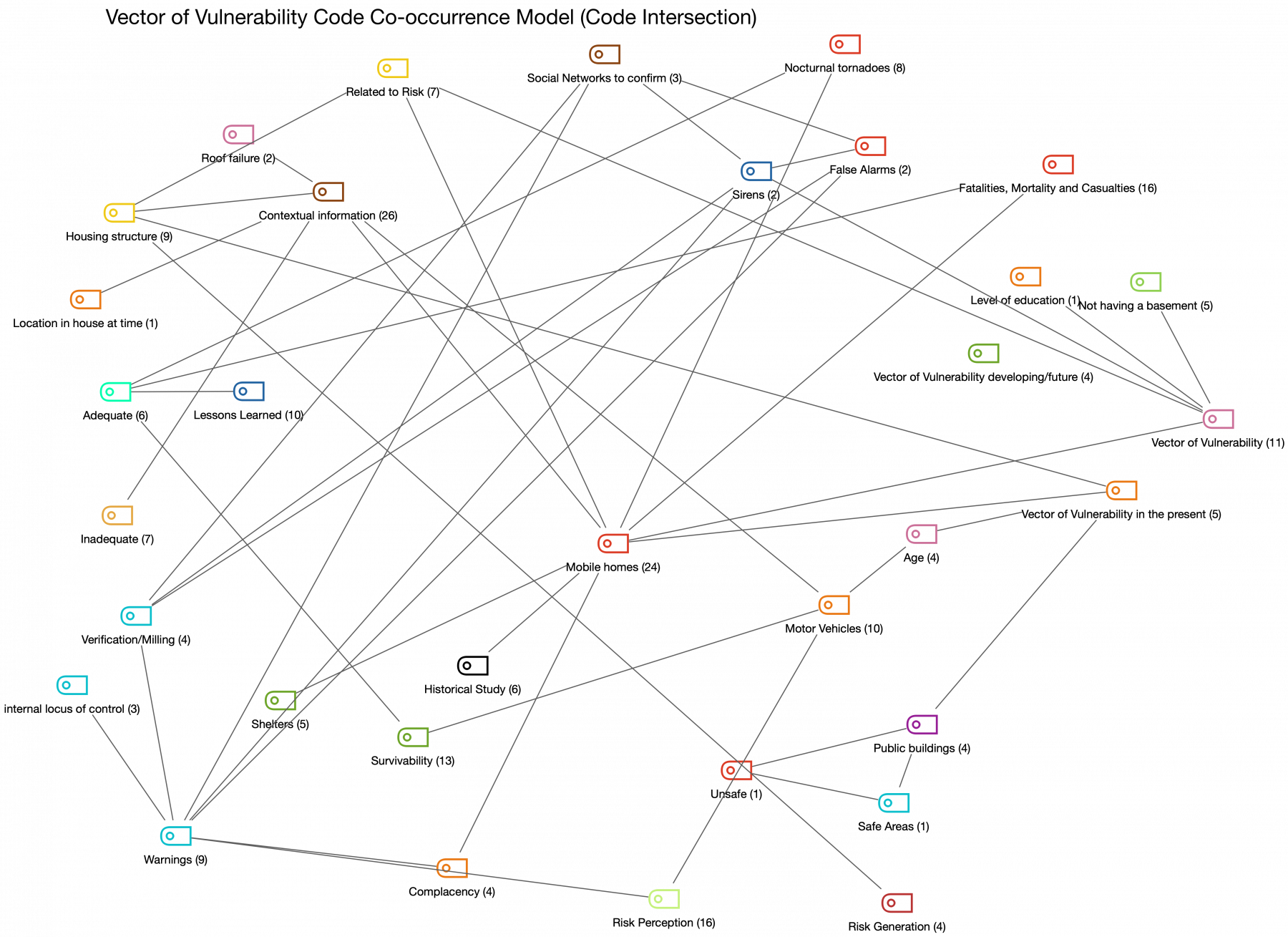

Analysis of literature highlighted the multiple vulnerabilities that drive increased risk of loss of life or injury. These do not exist in isolation but conspire together to weaken survivability outcomes. In order to understand these and frame them in a manner that acknowledges their complexity, a new terminology was needed. Consequently, vector of vulnerability is defined as a vulnerability resulting from a specific vector that improves or worsens the impact for individuals in the path of a tornado. In the same way that a mosquito is a vector for diseases such as malaria, dengue fever and others, by dint of the way it carries and spreads these diseases, a tornadic vector of vulnerability is one that has the capacity to carry and spread increased vulnerability, with each of vector having their own weight in terms of strengthening or weakening survivability of those in the path of a tornado.

This weighting is likely to be reflected by the way each vector increases fatality rates or enhances survivability. There is also complexity within each vector of vulnerability as they are also impacted by access to finances, social networks and education and learning opportunities. Although many different vectors of vulnerability were identified, there were certain vectors that were seen as having the greatest impact on driving mortality:

- Location in a house or building (floor, near a window etc.,);

- Warnings given that may have been adequate, inadequate or not received;

- Mobile homes;

- Access to a basement in permanent homes;

- Access to a shelter.

Figure 1, illustrates how the threads currently connect as vectors of vulnerability. If severed, tornado fatalities and their impacts might be reduced by tackling vectors with the highest impact. Returning to our mosquito and malaria example, this would include having mosquito nets (with and without DEET, therefore showing further layers of complexity, cost and risk assessment by an individual), as well as simpler and finance free measures such as removing standing water where mosquito larvae are laid. The questions we need to ask and provide reasonable solutions for are:

- What are the most effective ways of reducing vectors of vulnerability?

- Which vectors have the highest weight, cost and practical applications which might encourage or hinder actions to counteract them?

Figure 1: A MaxQDA generated code relations map showing the interaction of codes for Vectors of Vulnerability

High frequency vectors of vulnerability such as mobile homes, are also made up of a variety of sub-vectors that include, mobile homes’ construction, lack of stability when not tied to foundations, age, lack of maintenance and over-confidence in their ability to withstand tornadic forces.

There is also evidence that residents of mobile homes are also aware of the appropriate action to take when a tornado occurs but don’t have access to shelter. Nevertheless, even following the correct advice can have tragic consequence when tornadoes directly hit and have high wind speeds.

The literature indicated that people are acutely aware of the risks, how these impacts on their vulnerabilities and prepare appropriately within the bounds of their resources (such as access to shelter, transport, alternative measures, hazard awareness and safety actions). This tends to refute arguments made regarding ‘complacency’ among residents towards tornado preparation and actions (e.g. Biddle, 1994 and Ashley, 2007).

This leaves the thorny issue of how to tackle some of the gaps that still exist and make mobile home residents so vulnerable to tornadoes to the extent that fatality rates are up to 30 times that of a resident of a permanent home. It is likely that the answer is not to suppose, theorise or expostulate, but to directly connect with communities with large mobile home populations. The phrasing of this last sentence is chosen carefully. There aren’t really ‘communities’ of mobile home residents, especially in the SE United States, but there are communities and networks bound by common experience, religion and culture. Perhaps the answer is to have research focus led by asking these communities that happen to reside in mobile homes what they need.

Theme Three: Risk

Risk as a part of the overall story of tornado epidemiology was focused around risk perception, with a specific focus on tornado warnings. This is because the issue is inextricably linked currently to temporality. This temporality was deemed to be at a number of times scales:

- Minutes in terms of tornado warnings given;

- Hours in terms of tornado watches;

- Diurnally in terms of day or night tornadoes, with many nocturnal tornadoes going ‘unwarned’ from the perspective of citizens who may be asleep when warnings are given;

- Seasonally in terms of expectations of citizens and the idea of a tornado season.

There may be improvements in communication of risk (in terms of watches, warnings and how citizens react to them) that can be achieved, but there are also issues of how information is received, whether it is trusted and most importantly, the options that citizens have to act upon warned tornadoes. There are known vulnerabilities, and these are inextricably linked to the nature of the hazard (in terms of its magnitude) as part of the conceptual risk equation Risk= Hazard X Vulnerability (Burton et al, 1978 and Wisner et al, 2004).

The literature also points out that many citizens are aware of risk and take appropriate action such as going to an interior bathroom or closet but that the structural integrity of the mobile home coupled with poor anchorage and maintenance of tie-downs struts in some cases are drivers of risk and are separate vectors of vulnerability that enhance that risk.

Large loss of life in mobile homes and indeed in permanent homes is also linked to lack of access to shelters. It is likely that this gap might be closed by allowing communities to map their own risk (better understanding it) as well as evaluating their own capacities in terms of sheltering options that currently exist locally.

Theme Four: Capacity

Something that is missing in the literature is capacity of individuals. This concept needn’t be nebulous and intangible, but real and actionable behaviours. These might come from initiatives in which communities of practice (citizens, emergency managers, the weather enterprise and researchers) learn to work together to identify what capacities currently exist and building upon them to enhanced future capacities.

A key part of identifying capacity is knowledge about the survivability of tornadoes. One of the principal guiding aims of the research was to provide a baseline for survivability as well as acknowledging and understanding what drives fatalities. But baselines require a knowledge of exposure rates in tornado events so that there is an understanding of both fatality rates and survivability rates. This is an area of future research that is likely to reap significant benefits and perhaps needs to be a research priority.

Key to reducing individual, and by extension a community’s vulnerability is by enabling them to become more resilient to the shocks that a potential disaster may force upon them. But this requires learning rather than education or knowledge transfer that are often grasped for improving resilience. Consequently, socially constructed and transformative learning with the potential to build self-efficacy has an important bridging role to play in allowing communities to prepare for and adapt to such events, irrespective of wealth, status and level of formal education.

Transformative Learning (TL) approaches facilitate learners to question their assumptions, which then change as a result experience. Mezirow and Taylor suggested that it is teaching for change (Mezirow and Taylor, 2009), while Armitage et al. noted that Mezirow (1995) proposed that, “an outcome of transformative learning is the development of liberated, autonomous and socially responsible individuals with the capacity to move from critical examination of their experiences to action” (Armitage et al, 2007, p.88).

In particular, transformative learning, although challenging, has the potential to empower individuals to adapt to shocks and surprises that disasters may cause. As a result, individuals, families and groups may evolve into communities of practice with better coping mechanisms allowing them to view natural hazards as inevitable but disasters as not.

Currently capacity is not a widely expressed as underpinning survivability. In order to understand and enhance capacity there may be a need to augment our collective approach. This means moving away from from top-down and expert led approaches to bottom up and embedded ones, allowing for experts to contribute from across communities. By widening communities of practice, it is more likely that we will be able to identify and close value-action gaps between intentions and behaviour, building capacity to survive tornadoes as an outcome.

Justin Sharpe, PhD, Research Scientist at OU-CIMM and the social science co-ordinator for the VORTEX-SE project.

References

Armitage, D., Berkes, F., Doubleday, N. (Eds.), 2007. Adaptive Co- Management: Collaboration, Learning and Multi-Level Governance. University of British Columbia Press, Vancouver.

Ashley, W. S. (2007). Spatial and temporal analysis of tornado fatalities in the United States: 1880-2005. Weather and Forecasting, 22(6), 1214–1228. https://doi.org/10.1175/2007WAF2007004.1

Biddle, M. D., 1994: Tornado hazards, coping styles, and modernized warning systems. M.A. thesis, Dept. of Geography, University of Oklahoma, 143 pp.

Brooks, H. E., & Doswell, C. A. (2002). Deaths in the 3 May 1999 Oklahoma City tornado from a historical perspective. Weather and Forecasting, 17(3), 354–361. https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0434(2002)017<0354:DITMOC>2.0.CO;2

Burton, Ian, Robert W. Kates, and Gilbert F. White. 1978. The Environment as Hazard. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hammer, B., & Schmidlin, T. W., 2002. Response to warnings during the 3 May 1999 Oklahoma City tornado: Reasons and relative injury rates. Weather and Forecasting, 17(3), 577–581. https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0434(2002)017<0577:RTWDTM>2.0.CO;2

Mezirow, J. (1995) “Transformative Theory of Adult Learning.” In M. Welton (ed.), In Defense of the Lifeworld. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Mezirow, J., and Taylor, E. W. (2009). Transformative learning in practice: Insights from community, workplace, and higher education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Wisner, Ben, Piers Blaikie, Terry Cannon, and Ian Davis. 2004. At Risk: Natural Hazards, People’s Vulnerability, and Disasters. New York: Routledge.