Researcher Kim Klockow-McClain absorbs the sights and sounds around her at Providence Baptist Church in Lee County, Alabama — almost one month since tornadoes devastated the community.

Klockow-McClain wants to tell people’s stories. They guide her effort to create a more complete picture of storms — not just how they happen meteorologically, but the impression they leave on people’s lives.

As a societal impacts researcher at the University of Oklahoma Cooperative Institute for Mesoscale Meteorological Studies, her work supports NOAA’s National Severe Storms Laboratory to improve the tools used by NOAA National Weather Service forecasters.

She wants to learn how emergency management agencies, broadcast meteorologists and NWS forecasters work together in an attempt to impact the public, how they operate individually and how current practices ultimately affect severe weather safety messages the public receives.

“It will kind of be the end of the story for this tornado path that I’ve been following through Alabama and into Georgia.”

So on a dewy Tuesday morning, Klockow-McClain stands among 23 white crosses on the church’s south lawn. The crosses are a symbol of remembrance — of each person who died on March 3 after tornadoes tore through the area. The memorial is disheveled from a storm the night before but some items placed at the base of each cross remain — including a jar of peanut butter.

“You can just imagine it was their loved one coming up to their memorial saying, ‘I know you would want your peanut butter,’” she said, tears forming in her eyes.

She takes a moment, lightly hugs the manilla folders filled with her surveys and questions, wipes her eyes and walks toward the church.

A visceral need

Klockow-McClain has a visceral need to visualize things. She says as a geographer she has to see things — maps, pathways, connections. Making those connections helps her build a map.

She visited the memorial first to build that piece of her research map and connections.

“I’m trying to understand the setting, the people and the place — who they are, who they were — the people who are gone,” Klockow-McClain said. “I couldn’t come here and not see the memorial. Ultimately, this is about the families who were left behind and the people who died.”

Her research is part of the Verification of the Origins of Rotation in Tornadoes EXperiment-Southeast, or VORTEX-SE, funded by NOAA.

VORTEX-SE is an effort to understand how environmental factors characteristic of the southeastern U.S. affect the formation, intensity, structure, and path of tornadoes in this region. The experiment will also determine the best methods for communicating the forecast uncertainty related to these events to the public, and evaluate public response.

For three days Klockow-McClain traveled the path of the March 3 tornado through Alabama and Georgia, meeting with those involved in alerting the public and locals who were personally impacted.

“It will kind of be the end of the story for this tornado path that I’ve been following through Alabama and into Georgia,” Klockow-McClain said.

Her research is focused on how messages coming from an Integrated Warning Team — emergency managers, broadcasters and forecasters — serve those living in manufactured and mobile homes, or whether further collective activities may need to be undertaken.

“When talking to all of the vested parties — emergency management agencies, broadcast meteorologists, forecasters and the public — you see places of great opportunity,” Klockow-McClain said. “We as researchers can release the best severe weather technologies for our partners, but if people don’t use, can’t use them and don’t want them for reasons we don’t understand — that helps no one.”

Bringing purpose

Klockow-McClain’s public response survey work first began in 2011 in Pleasant Grove, Alabama, about two hours from Providence Baptist Church.

Eight years later she revisited where her career began. As she navigates the curves of a rural road, she recounts one of the first times she interviewed someone who had witnessed a deadly storm. The person realized a tornado was near because they felt and heard debris falling on them while they were working on their vehicle.

Klockow-McClain spoke to that individual for nearly an hour in 2011. Now, sitting in the driver’s side of an SUV and staring at that person’s former home, she retells their story.

This person was one of 70 Klockow-McClain interviewed in less than one week. They heard meteorologists talk about an elevated weather risk on that day but didn’t think too much about it. That was until while working on their vehicle outside they described house insulation falling from the sky. Klcokow-McClain said the person ran inside their house, grabbed their significant other and animal and shoved them all in the bathtub. That move saved their lives. Describing the hours to come — losing neighbors, seeing houses gone around them — Klockow-McClain said she will never forget her hour-long conversation with that individual.

“I’m just creating a space for them to talk. I recognize that offers value to people. I use a method that involves care as a core principle. I feel like I’m doing something that matters.”

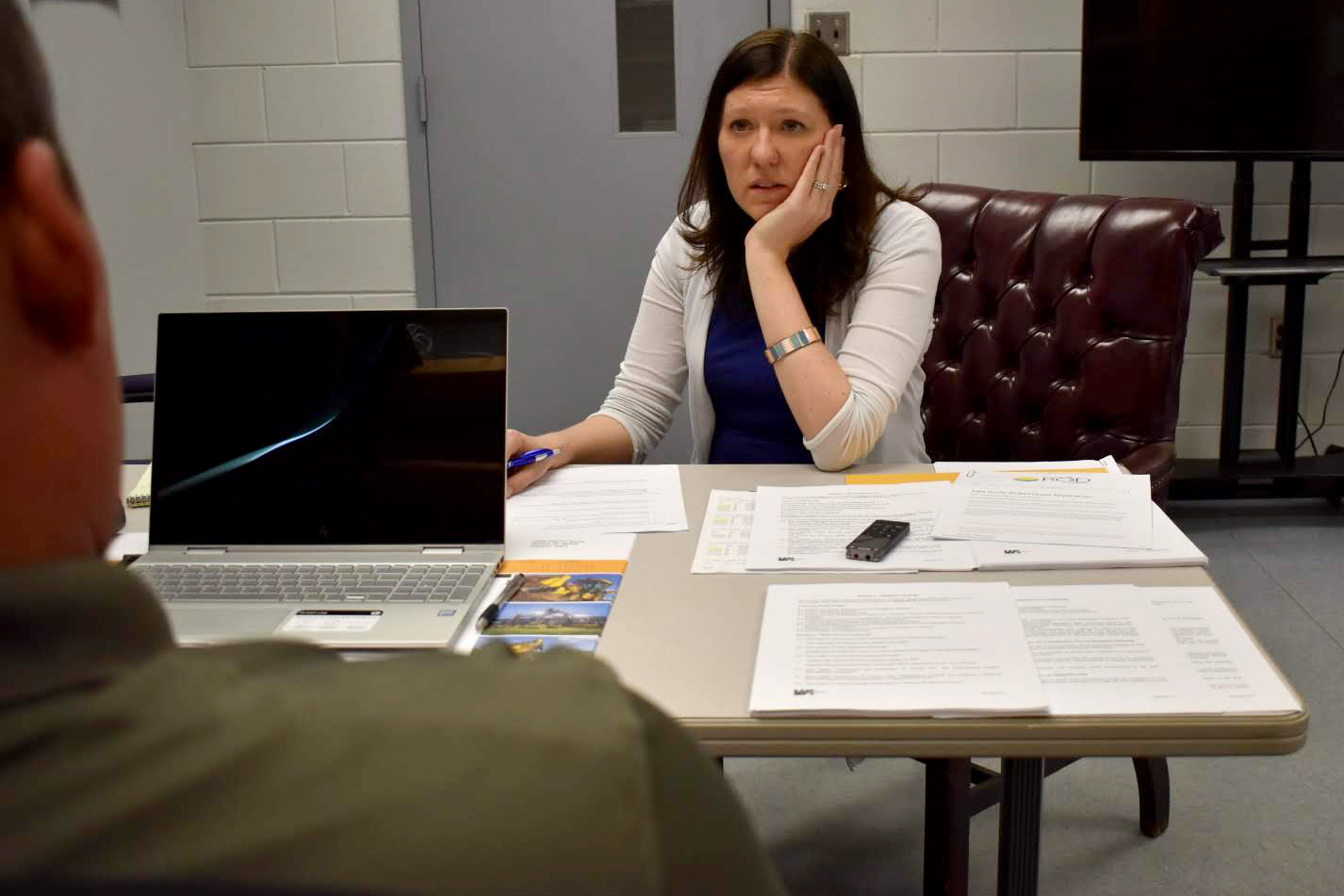

Inside Providence Baptist Church, Klockow-McClain is in a similar situation. She sits with an interviewee as they recount graphic details, highlighting every megapixel of that photographic day in March. All of the stories she’s heard don’t impact her personally. Klockow-McClain doesn’t let them. Instead, those stories bring her purpose.

“In the role as interviewer, you’re equal parts researcher and counselor. I’m just creating a space for them to talk,” Klockow-McClain said. “I recognize that offers value to people. I use a method that involves care as a core principle. I feel like I’m doing something that matters.”

She specifically chose to visit Alabama and Georgia nearly one month after the event because the crisis stage was ending and people were slowly attempting to recover a sense of normalcy.

Helping people feel heard

Klockow-McClain understands her research with devastating tornadoes can be emotionally taxing, but she never views it that way.

“I’m grateful I get to tell these stories,” she said. “As a meteorologist, you see these things happen and it can feel terrible to feel like you can’t do anything. So for me, to be able to sit there and feel like I’m helping them by helping them feel heard and their story matters by being a part of a bigger picture — that is helpful to me.”

She lets the person being interviewed steer the interview, no matter how graphic the story. Klockow-McClain said she wants to start in their shoes as people share what is most important to them. She listens to them verbalize the items that come to their minds as they help her understand their frame of mind and perspective.

“Research isn’t just about going out and collecting observations of wind, precipitation and atmospheric factors,” she said. “It’s about relating to people deeply enough that you really and truly can understand the context of what they’re telling you and fill this role of having some sympathy that’s meaningful to them for what they’ve experienced because they’ve gone through something very difficult. To come in and just dispassionately have a checklist or survey wouldn’t feel right to me.”

Generating a diagnosis

Klockow-McClain spent several hours speaking with volunteers at the church before following their suggestions to see the tornado damage in person.

She drove for less than 15 minutes before she saw signs of the damage and suddenly she was in the thick of it. Power lines were still down in areas. Piles of debris sat by the road as crews worked to clear side roads. Those living nearby watched for looters, which was a consistent issue after the storms.

Klockow-McClain hopes her research will lead to a better understanding of the needs of specific communities in the southeast to reduce tornado deaths in that area of the United States. Her research is aimed at generating a diagnosis that could ultimately lead to an effective treatment. A part of that is telling people’s stories.