If you pay enough attention to my twitter feed, you may have noticed my miniature existential crisis about choosing to read journal articles for fun during a Superbowl party…

[tweet https://twitter.com/eeeeelizzzzz/status/1092254485521596416]

Well… I don’t have any regrets. Actually the pair of articles I was reading that day are pretty important. Especially in light of the #MeToo movement and stories like this one. The first of the pair is Clancy et al. (2014), which summarized responses to a survey to characterize the lived experiences of field scientists related to gendered experiences, sexual harassment, and sexual assault. A follow up study (Nelson et al. 2017) uses the same survey data alongside follow-up extended interviews with a subset of respondents to further explore the field-site environment and the experiences of scientists in it.

Disclaimer: I am not a social scientist in any shape or form, but I am a field scientist. I found these reads to be quite relevant and encourage others to read both articles in full for themselves (links are provided below). Here I simply offer a summary of what I found intriguing about the pair of studies.

Fieldwork is important! Fieldwork attracts many to science (just think of the budding meteorologists that want to be storm chasers!) and it generates a substantial portion of science research for fields like meteorology. We know that researchers in disciplines where field-based study is active tend to publish more articles and attract more research funding than disciplines without active field study. We also know the people most often put in charge of field sites (e.g., senior research scientists or faculty members) are not commonly trained in human-related issues that arise in the field. Clancy et al. (2014) list some of the lacking skills as conflict management, negotiation tactics, and resolution skills. In many ways, the perception is that successful field deployments collecting quality data are prioritized over the experience of the people in the field doing the work.

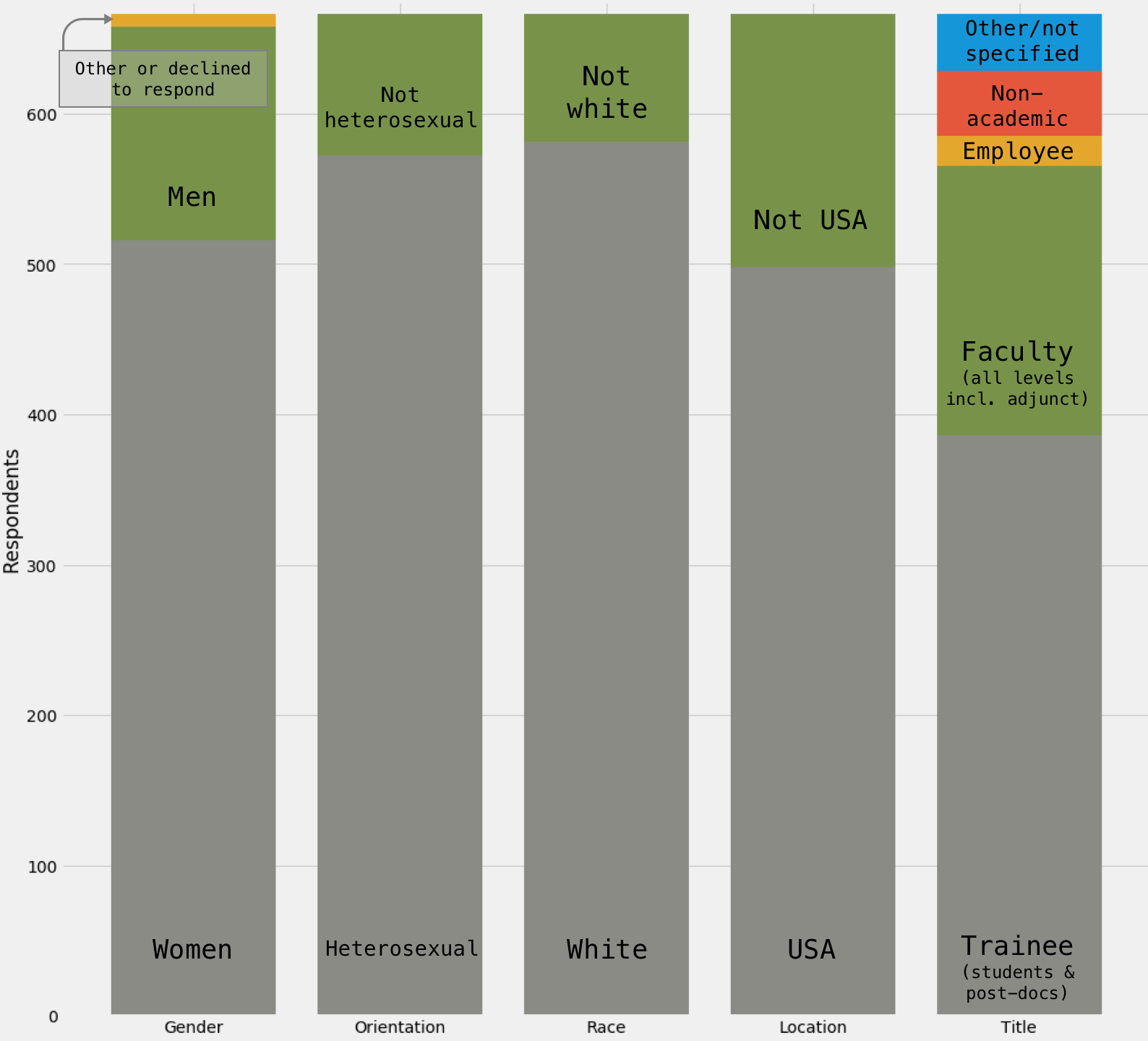

Several studies (references in both papers) have focused on defining or quantifying the workplace environment in many perhaps more traditional workplace settings, and in these studies (and in recent media buzz) sexual harassment and assault have received large amounts of attention. In an effort to document scientists’ experiences in the field, a survey of 666 respondents was conducted, which is the main focus of Clancy et al. (2014). The survey and following analysis focused on 3 broad key questions: 1) do respondents experience harassment and assault at field sites? If so, 2) who are the targets and perpetrators of harassment and assault? And 3) do field sites have codes of conduct and effective reporting mechanisms available to targets of abuse?

Clancy et al. (2014) includes much more detail than I will here about the survey instrument, interpretation, statistics, sampling and potential limitations of the approach. Here are a handful of caveats that I found interesting. First, they note the particular importance of multiple perspectives in defining the climate of a field site, since the target is not the only one to ‘experience’ assault or harassment; bystanders may also be influences by witnessing the event(s). Second, there are several open questions about the survey’s resulting sample. Since harassment and assault are intense experiences, individuals may be more or less likely to complete the survey. Those with strong negative experiences may be more likely to participate than those without, but on the other hand, some with strong negative experiences may be less likely to participate to avoid addressing painful memories. Snowball sampling (e.g., some people may be compelled to forward the survey to people they know had negative experiences) may also play a role here.

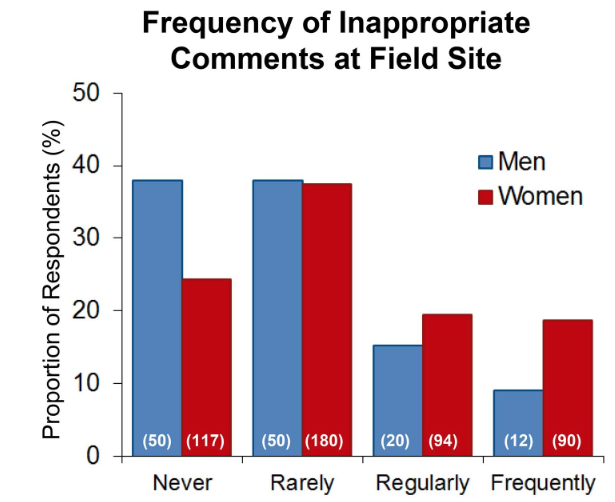

Results of the survey can be described via three figures presented in Clancy et al. (2014) which depict the frequency of inappropriate comments, the sources of inappropriate behavior, and a summary of respondents overall experiences. First, let’s look at the frequency of inappropriate sexual comments at field sites as indicated by respondents.

Only 25% of survey respondents indicated they had never witnessed or experienced inappropriate or sexual comments at their field site. The study also reports 64% of responded personally experienced sexual harassment and over 20% experienced sexual assault. The gender breakdown in indication of frequency of inappropriate comments is clear, with men more likely to report such instances as more rare and women as more frequent. Is this a result of perception? Is it just that women are targeted more often? Is it a sampling issue? This is unclear, but interesting to consider.

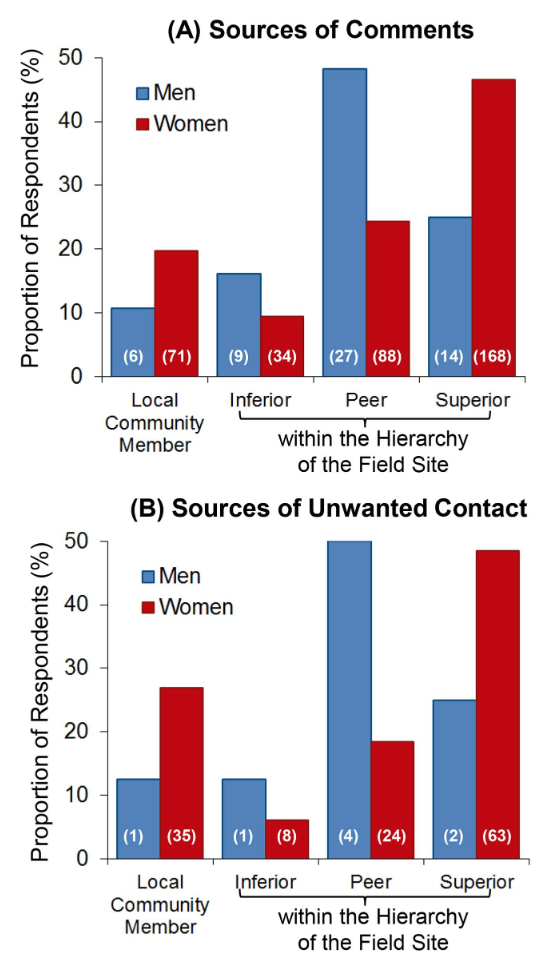

I found the analysis of the target-perpetrator matches one of the most interesting parts of Clancy et al. (2014). In the survey dataset, women were much more likely to indicate experiences of sexual harassment or assault than men, and the perpetrators differed depending on the target’s gender. Harassment and assault aimed at men was more often perpetrated by peers (described as horizontal dynamics), while instances aimed at women were more often perpetrated by superiors (described as vertical dynamics). I find this difference in dynamics surprising and very interesting. Why is this the case? The authors don’t offer much insight into that (as it would surely be speculative), however they do suggest that harassment or assault from superiors may result in higher job dissatisfaction and attrition rates than from peers. I suppose the analogy is that a horrible boss is worse for your work life and growth potential than horrible co-workers. Perhaps this is a part of the reason we see a mismatch in growth rates of female STEM students/graduates and female STEM professionals?

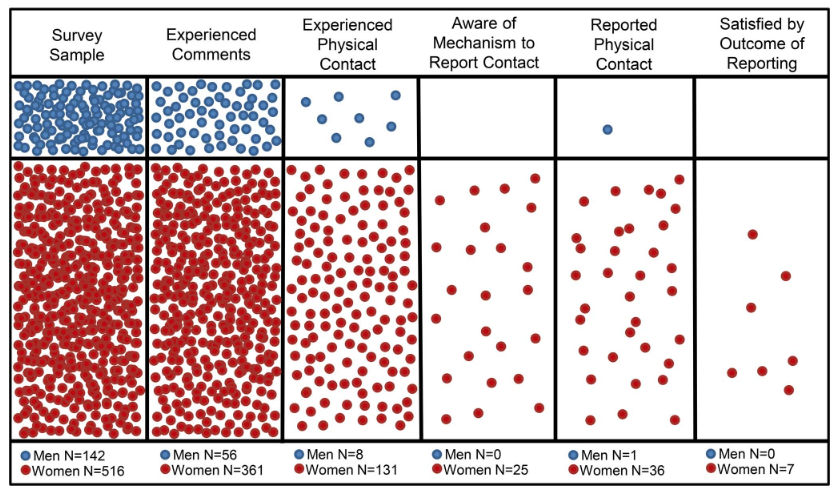

Clancy et al. (2014) reported that there was generally very limited awareness or understanding of policies and reporting procedures. Only 18% of respondents that indicated experiences of harassment or assault indicated that they knew of a reporting mechanism at the time of the incident. Across all demographics, incidences of reporting were low with even lower rates of satisfaction with the outcome of those reports.

A lot can contribute to a choice to or not to report, but awareness or availability of a policy and mechanism should not be one. This brings us nicely to the follow-up study, Nelson et al. (2017). Extended interviews were conducted with 26 of the original survey respondents to shed more light on “how such experiences shape perspectives of the STEM research climate, affect individual motivation and ability to continue in fieldwork-based disciplines, and influence career trajectories.” Through thematic analysis of these interviews, three main results became apparent: 1) field experiences differ according to presence or absence of rules, and consequences if rules were violated, 2) hostile environments and negative experiences influenced careers, and 3) egalitarian behaviors and enforcement of rules governing behavior enhanced field experiences for respondents.

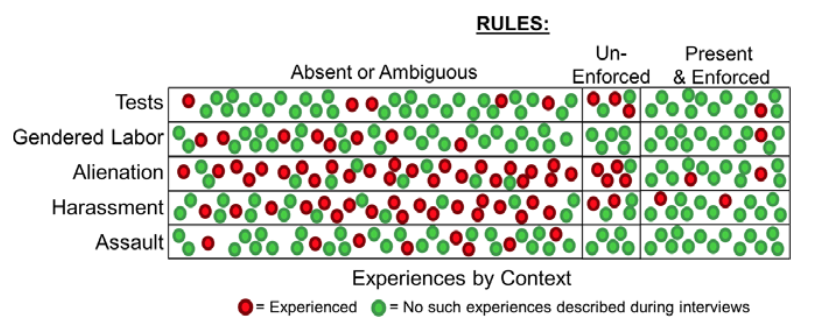

The first result suggests that rules and enforcement are key. As was first identified from the survey results, few respondents were aware of or understood the policies and reporting mechanisms in place to address behavior in the workplace let alone in a field setting. Three ‘rule states’ emerged from interviews: rules absent or ambiguous, rules present but unenforced, rules clearly present and enforced.

Negative behaviors that were indicated in interviews were categorized into 5 classes. Two classes covered the same type of harassment and assault discussed above, but the other three include additional instances that make a field setting less than inclusive. “Tests” include behavioral benchmarks which are intended to define the in/out group dynamics; who is in the “in-crowd” in a group setting. An anecdote included in Nelson et al. (2017) gives an example of testing behavior:

“We would do these really, really long days but we wouldn’t be warned when they were coming, they would just happen and so I wouldn’t bring enough food. . . And I would try to vocalize, “I am tired. I can’t go any further. I need to eat.” . . . The second time I spoke up, there were the other two girls who were quick to say, “Yeah, we’ve been out a really long time, it’s 8:00 p.m., let’s go eat.” We started getting snide comments like, “Oh, well the ladies are hungry so I guess we have to leave.”

Gendered labor is exactly what is sounds like: assigning tasks to individuals based on stereotypes concerning their perceived gender, such as assigning women in the field to cook and clean. Alienation is described as a feeling of isolation from others in the field including during data collection or work tasks and social settings. The information gathered from interviews showed a fairly direct association between the clarity and application of rules and expectation to resulting behavior at field sites. At sites where rules were poorly defined or not enforced, negative behaviors occurred much more frequently than at sites where the rules were clear and enforced.

Related to the speculation about the connection between vertical dynamics in harassment reported in Clancy et al. (2014) and women leaving STEM fields, the second main result suggested that hostile environments (which thrive in the absence of clear and enforced rules) negatively influence careers for those that are the target of hostile behaviors. Several interviews noted that it isn’t so simple as to just leave the hostile field site. Many science sub-fields are quite small after all. One respondent that left a field site due to a hostile colleague said:

“Because I work in this area of the world and work at certain sites where he is pretty well known, it kind of became clear that I was going to have to play along a little bit of the political game where future research would have to. . . . I’d have to be careful about how I interact with this person. . . . Because my research was now starting to be centered around this area and he had this reputation and everyone knew him. So I had basically an arm’s- length professional connection with this person but then, also, he sort of started to be like as if he expected me to become the next mistress.”

For other respondents, the impact of the hostile field environment as to lead to significant alteration of their career trajectory, with reports of individuals changing jobs, changing fields, or dropping out of training programs all together.

But there’s hope! Not all interviewees reported negative experiences! In fact, those that reported positive experiences reported enhancements to their careers and increased paths into leadership roles. Positive field site descriptions included three characteristics: sites were perceived as fair, the conditions for living and working were intentionally designed to be safe, and those in charge anticipated issues and made clear avenues for reporting. Two relevant anecdotes were included in Nelson et al. (2017) that are worth repeating here:

Anecdote 1: “The field director, on the first day, gathered everyone around and even though he was very casual about it, he welcomed us to the site and listed the ground rules. . . . He made it seem that we were all at the same level and if there were any problems, come to him. So he made it clear how he was going to act as a field director. Sort of what his goals were this field season and how we should all behave and how we should be respectful of others and don’t goof off but we were also going to have fun in the evenings and when we’re not working. We shouldn’t be afraid to come to him with any problems, if they were to occur. And when a problem did occur, I know he took care of it or handled it appropriately.”

Anecdote 2: “It’s kind of like having the sex talk with your kids. No one wants to have that conversation because it’s awkward. And it is awkward because it’s not necessarily expected of you to sit down and lay out expectations in terms of field behavior but I think it’s worth getting it out of the way and having an honest conversation and I think it makes for a better experience overall for both the people who are running those field programs but also the people that are a part of the team.”

So it seems the power resides with those running field sites to make field work more inclusive, and approachable. Not a surprising result in general, but I think it is an important component of field management and field experiement design that gets overlooked. Should safety procedures and codes of conduct, including consequences and reporting infrastructure be part of funding proposal development?

As a field scientist, I think of the barriers to the field often. Why am I still one of very few (or sometimes still the only) woman in the room planning field outings? Why don’t we make considerations for accessibility to the field for those that aren’t white cisgender men? For example, I have more than once had to remind colleagues that it’s very difficult for me as a female to privately pee outdoors in the open land of the Great Plains when there’s no tree in sight, or that I need a restroom when I happen to menstruate (no one EVER thinks of this).

I LOVE field work. It’s invigorating, it’s inspiring, it’s humbling. It’s my favorite part of my job, and I want to give this awesome opportunity to others. Where do we start?

I don’t have answers, but I think talking about it is a good start. There’s some great discussion on the twitter verse about this. I’ll link some threads and accounts here.

[tweet https://twitter.com/GonzoScientist1/status/1100936895909912577]

[tweet https://twitter.com/anthrostudies/status/953970818480005121]

Accounts to check out: @McLNeuro and @MeTooSTEM[Edited to remove references to these twitter accounts. As reported in several news outlets, this individual and the initiative they ran centered the individual, was damaging to several folks, and ended up spreading false narratives. I like many others thought this was a genuine effort and apologize for suggesting the account. An important lesson was learned by many, including myself.]

Have some thoughts or want to discuss… check out my contact page, or go find me on twitter @eeeeelizzzzz

References:

Clancy, K. B. H., R. G. Nelson, J. N. Rutherford, and K. Hinde, 2014: Survey of academic field experiences (SAFE): trainees report harassment and assault. PLoS One, 9, e102172.

Nelson, R. G., J. N. Rutherford, K. Hinde, and K. B. H. Clancy, 2017: Signaling Safety: Characterizing Fieldwork Experiences and Their Implications for Career Trajectories: Lived Experiences in the Field. Am. Anthropol., 119, 710–722.